Black Hawk by Roger L. Nichols

Black Hawk, Makataimeshekiakiak, or Black Sparrow Hawk, a Sauk tribal leader, was born at Saukenuk, the largest Sauk village, near the mouth of the Rock River in western Illinois in 1763.

Black Hawk, Makataimeshekiakiak, or Black Sparrow Hawk (1763?–October 3, 1838)

He reached adulthood as fundamental changes reached the Indians of the upper Mississippi Valley. For generations, tribes in that region had dealt with French, British, and Spanish traders and officials, but few of those people lived near them. With American independence in the 1780s, citizens and government negotiators surged westward. By 1804 the United States had purchased Louisiana, the region between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Within a few months American negotiator William Henry Harrison had persuaded a few Sauk leaders to cede all of their territory in present-day Illinois and Wisconsin to the federal government. That treaty infuriated many of the Sauk, who rejected its legality. The treaty dispute between the tribe and the government divided the Sauk and their allies, the Meskwaki, for a generation, and Black Hawk became a focal point for anti-American ideas and actions. During the late 18th century, he became a recognized warrior and leader, organizing and leading frequent attacks against enemy tribes, and gaining a solid core of followers within his society.

American entrance into Iowa and Illinois and efforts to prevent Sauk raids on other tribes infuriated the young warrior. He turned increasingly to the British for support and encouragement. During the War of 1812, he led several hundred warriors to Detroit. From there they fought against the United States in Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio. Returning to Saukenuk in late 1813, the warriors learned that Keokuk had been appointed war leader there in their absence.

To Black Hawk's annoyance, the younger man's superior oratorical skills helped him dominate tribal affairs and relations with the United States for several decades. Nonetheless, Black Hawk continued to direct military campaigns. In May 1814 he defeated Major Zachary Taylor and more than 400 U.S. troops near the mouth of the Rock River. Sporadic raids continued into 1815, and the Rock River Sauk refused to meet American negotiators at Portage des Sioux that year. In 1816 they signed another agreement under threat of American attack. This reaffirmed the disputed 1804 treaty, but Black Hawk and several others refused to sign the new accord.

From 1816 to 1829 white pioneers moved into Sauk territory, and by the latter year had begun to seize land at Saukenuk. By that time most of the Sauk and Meskwaki had agreed to stay west of the Mississippi in Iowa and Missouri, and only a minority chose to return east to Illinois. That group, referred to by American officials as the British Band because of their supposed reliance on officials in Canada, included discontented Sauk, Meskwaki, and some nearby Kickapoo who came together to defy Illinois officials' demands that they leave the state. In June 1831 General Edmund P. Gaines, commanding army regulars, forced the British Band from Saukenuk into Iowa.

That winter the Sauk-Winnebago prophet Wabokieshiek, or White Cloud, invited the British Band to join his village up the Rock River in northern Illinois, so in April 1832 Black Hawk led perhaps 1,800 people back into Illinois. They hoped to establish a new village, but the pioneers and Illinois politicians denounced the move as an "invasion."Soon militiamen and U.S. Army troops began to pursue the British Band as they moved up the Rock River valley into southern Wisconsin. After weeks of scattered Indian raids and fruitless hunting for their quarry, the whites overtook the Indians at the mouth of the Bad Axe River and killed most of them, ending the conflict.

The government imprisoned Black Hawk and several British Band leaders at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis in 1832. The next year it sent several of them east to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. After taking the captives to several large eastern cities, authorities sent them home. In August 1833 Black Hawk had to agree to accept Keokuk's leadership in the tribe and to remain at peace.

On October 3, 1838, Black Hawk died peacefully. To him, Americans represented a selfish, greedy, and dishonest society. In opposing them, his behavior represented the actions of a patriotic Sauk. He sought to protect the Sauk values and way of life. By the 1830s, however, the frontier situation in his home region had changed so drastically that those ideas existed mostly in his memory.

Sources For a view of how the Black Hawk War has been treated, see Roger L. Nichols, "The Black Hawk War in Retrospect," Wisconsin Magazine of History 65 (1982), 239–46. For a subsequent fully contextualized account of the Black Hawk War from the American Indian perspective, see Kerry Trask, Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America (2006). Roger L. Nichols, Black Hawk and the Warrior's Path (1992) is the only full biography available. Roger L. Nichols, Black Hawk's Autobiography (1999) is one of several editions of that account.

This research from Nichols, Roger L. "Black Hawk, Makataimeshekiakiak, or Black Sparrow Hawk" The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, 2009.

Monday, December 31, 2018

Sunday, December 30, 2018

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Native Americans capture Quaker Frances Slocum 1773-1847

From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries.

Frances Slocum (1773-1847), called Maconaquah, "The Little Bear," an adopted member of the Miami tribe, was taken from her family home by the Lenape in Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1778, and raised in the area that became Indiana. Frances was born into a family of early Quaker settlers of the Wyoming and Lackawanna Valleys, near Wilkes Barre.

Her parents, Jonathan Slocum and Ruth Tripp, came to Pennsylvania from Warwick, Rhode Island. Frances had 11 siblings, among them brothers Ebeneezer and Benjamin. These brothers found her 59 years later living on an Indian Reservation near Peru, Indiana. Despite the pleadings of her brothers, Frances refused to leave her family. She had been married twice and was the mother of four children.

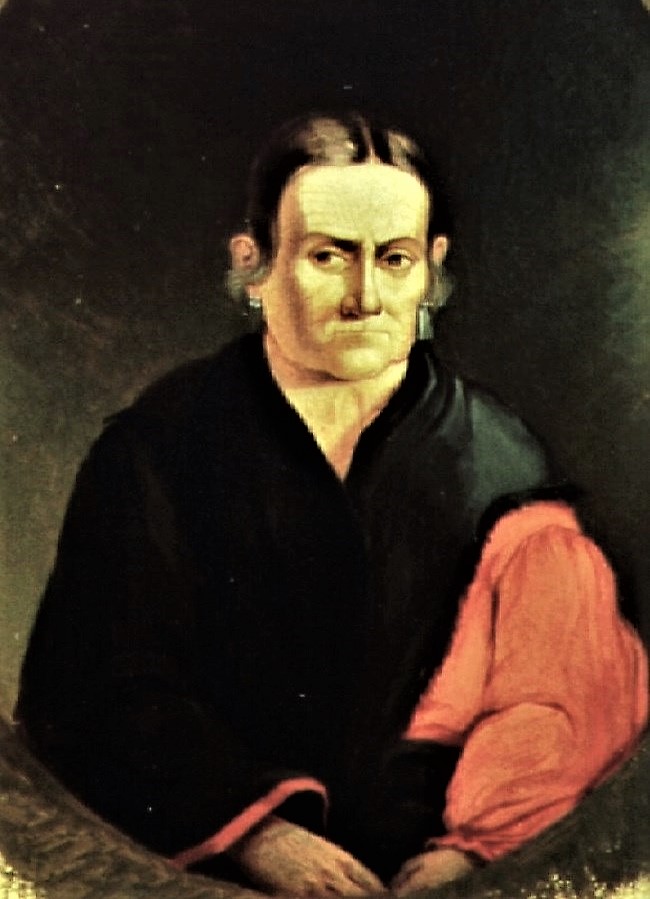

Painting of Frances Slocum by Jennie Brownscombe, from the book, Frances Slocum; The Lost Sister of Wyoming, by Martha Bennett Phelps, 1916.

"I can well remember the day when the Delaware Indians came suddenly to our house. I remember that they killed and scalped a man near the door, taking the scalp with them. They then pushed the boy through the door; he came to me and we both went and hid under the staircase.

"They went up stairs and rifled the house, though I cannot remember what they took, except some loaf sugar and some bundles. I remember that they took me and the boy on their backs through the bushes. I believe the rest of the family had fled, except my mother.

"They carried us a long way, as it seemed to me, to a cave, where they had left their blankets and traveling things. It was over the mountain and a long way down on the other side. Here they stopped while it was yet light, and there we staid all night. I can remember nothing about that night, except that I was very tired, and lay down on the ground and cried till I was asleep.

"The next day we set out and traveled many days in the woods before we came to a village of Indians. When we stopped at night the Indians would cut down a few boughs of hemlock on which to sleep, and then make up a great fire of logs at their feet, which lasted all night.

"When they cooked anything they stuck a stick in it and held it to the fire as long as they chose. They drank at the brooks and springs, and for me they made a little cup of white birch bark, out of which I drank. I can only remember that they staid several days at this first village, but where it was I have no recollection.

"After they had been here some days, very early one morning two of the same Indians took a horse and placed the boy and me upon it, and again set out on their journey. One went before on foot and the other behind, driving the horse. In this way we traveled a long way till we came to a village where these Indians belonged.

"I now found that one of them was a Delaware chief by the name of Tuck Horse. This was a great Delaware name, but I do not know its meaning. We were kept here some days, when they came and took away the boy, and I never saw him again, and do not know what became of him.

"Early one morning this Tuck Horse came and took me, and dressed my hair in the Indian way, and then painted my face and skin. He then dressed me in beautiful wampum beads, and made me look, as I thought, very fine. I was much pleased with the beautiful wampum.

"We then lived on a hill, and I remember he took me by the hand and led me down to the river side to a house, where lived an old man and woman. They had once several children, but now they were all gone—either killed in battle, or having died very young. When the Indians thus lose all their children they often adopt some new child as their own, and treat it in all respects like their own. This is the reason why they so often carry away the children of white people.

"I was brought to these old people to have them adopt me, if they would. They seemed unwilling at first, but after Tuck Horse had talked with them awhile, they agreed to it, and this was my home. They gave me the name of We-let-a-wash, which was the name of their youngest child whom they had lately buried. It had now got to be the fall of the year (1779), for chestnuts had come.

"The Indians were very numerous here, and here we remained all the following winter. The Indians were in the service of the British, and were furnished by them with provisions. They seemed to be the gathered remnants of several nations of Indians. I remember that there was a fort here.

"In the spring I went with the parents who had adopted me, to Sandusky, where we spent the next summer; but in the fall we returned again to the fort—the place where I was made an Indian child—and here we spent the second winter, (1780).

"In the next spring we went down to a large river, which is Detroit River, where we stopped and built a great number of bark canoes. I might have said before, that there was war between the British and the Americans, and that the American army had driven the Indians around the fort where I was adopted. In their fights I remember the Indians used to take and bring home scalps, but I do not know how many.

"When our canoes were all done we went up Detroit River, where we remained about three years. I think peace had now been made between the British and Americans, and so we lived by hunting, fishing, and raising corn...

"The reason why we staid here so long was, that we heard that the Americans had destroyed all our villages and corn fields. After these years my family and another Delaware family removed to Ke-ki-ong-a (now Fort Wayne). I don't know where the other Indians went.

"This was now our home, and I suppose we lived here as many as twenty-six or thirty years. I was there long after I was full grown, and I was there at the time of Harmar's defeat. At the time this battle was fought the women and children were all made to run north. I cannot remember whether the Indians took any prisoners, or brought home any scalps at this time. After the battle they all scattered to their various homes, as was their custom, till gathered again for some particular object. I then returned again to Ke-ki-ong-a. The Indians who returned from this battle were Delawares, Pottawatamies, Shawnese and Miamis.

"I was always treated well and kindly; and while I lived with them I was married to a Delaware. He afterwards left me and the country, and went west of the Mississippi. The Delawares and Miamis were then all living together.

"I was afterwards married to a Miami, a chief, and a deaf man. His name was She-pan-can-ah. After being married to him I had four children—two boys and two girls. My boys both died while young. The girls are living and are here in this room at the present time.

"I cannot recollect much about the Indian wars with the whites, which were so common and so bloody. I well remember a battle and a defeat of the Americans at Fort Washington, which is now Cincinnati. I remember how Wayne, or ' Mad Anthony,' drove the Indians away and built the fort.

"The Indians then scattered all over the country, and lived upon game, which was very abundant. After this they encamped all along on Eel River. After peace was made we all returned to Fort Wayne and received provisions from the Americans, and there I lived a long time.

"I had removed with my family to the Mississinewa River some time before the battle of Tippecanoe. The Indians who fought in that battle were the Kickapoos, Pottawatamies and Shawnese. The Miamis were not there. I heard of the battle on the Mississinewa, but my husband was a deaf man, and never went to the wars, and I did not know much about them."

George Winter 1810-1876 Francis Slocum

At the conclusion of this account of her capture, life and wanderings with the Indians for so many years, there was a pause for a few minutes. Every one present seemed deeply impressed with the story and the simple, artless manner in which it was related. In a short time the conversation was resumed, "We live where our father and mother used to live, on the banks of the beautiful Susquehanna, and we want you to return with us; we will give you of our property, and you shall be one of us and share all that we have. You shall have a good house and everything you desire. Oh, do go back with us!"

George Winter 1810-1876 Francis Slocum and daughter

"No, I cannot," was the sad but firm reply. " I have always lived with the Indians; they have always used me very kindly; I am used to them. The Great Spirit has always allowed me to live with them, and I wish to live and die with them.

"Your wah-puh-mone [looking glass] may be longer than mine, but this is my home. I do not wish to live any better, or anywhere else, and I think the Great Spirit has permitted me to live so long because I have always lived with the Indians. I should have died sooner if I had left them.

"My husband and my boys are buried here, and I cannot leave them. On his dying day my husband charged me not to leave the Indians. I have a house and large lands, two daughters, a son-in-law, three grand-children, and everything to make me comfortable; why should I go and be like a fish out of water?"

When her birth family could not convince her to leave the village, the Slocum family hired George Winter to paint a portrait of Frances & her daughter. Winter wrote descriptions of her family in his journals. The artist wrote of Frances in 1839, "Frances Slocum's face bore the marks of deep-seated lines. The muscles of her cheeks were like corded rises, and her forehead ran in almost right angular lines. There was indication of no unwanted cares upon her countenance beyond time's influence which peculiarly marks the decline of life...She bore the impress of old age, without its extreme feebleness. Her hair which was evidently of dark brown color was now frosted. Though bearing some resemblance to her family, yet her cheek bones seemed to bear the Indian characteristic in that particular - face broad, nose somewhat bulby, mouth perhaps indicating some degree of severity. In her ears she wore some few ear bobs."

Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst:University of Massachusetts Press, 2001)

Susan Sleeper-Smith, Enduring Nations: Native Americans in the Midwest, ed. R. David Edmunds (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008)

John F Meginnes, Women in America from Colonial Times to the 20th Century: Biography of Frances Slocum (New York: Arno Press, 1891, reprint 1974)

Stewart Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana: A Persistent People 1654-1994 (Indiana Historical Society, 1996)

James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985)

Jim J. Buss, "They Found and Left Her an Indian: Gender, Race, and the Whitening of Young Bear." Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Jun 01, 2008; Vol. 29, No. 2/3, p. 1-35.

"Winter's Description of Francis [sic]Slocum," Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History 1:3 (1905)

Frances Slocum (1773-1847), called Maconaquah, "The Little Bear," an adopted member of the Miami tribe, was taken from her family home by the Lenape in Pennsylvania, on November 2, 1778, and raised in the area that became Indiana. Frances was born into a family of early Quaker settlers of the Wyoming and Lackawanna Valleys, near Wilkes Barre.

Her parents, Jonathan Slocum and Ruth Tripp, came to Pennsylvania from Warwick, Rhode Island. Frances had 11 siblings, among them brothers Ebeneezer and Benjamin. These brothers found her 59 years later living on an Indian Reservation near Peru, Indiana. Despite the pleadings of her brothers, Frances refused to leave her family. She had been married twice and was the mother of four children.

Painting of Frances Slocum by Jennie Brownscombe, from the book, Frances Slocum; The Lost Sister of Wyoming, by Martha Bennett Phelps, 1916.

"I can well remember the day when the Delaware Indians came suddenly to our house. I remember that they killed and scalped a man near the door, taking the scalp with them. They then pushed the boy through the door; he came to me and we both went and hid under the staircase.

"They went up stairs and rifled the house, though I cannot remember what they took, except some loaf sugar and some bundles. I remember that they took me and the boy on their backs through the bushes. I believe the rest of the family had fled, except my mother.

"They carried us a long way, as it seemed to me, to a cave, where they had left their blankets and traveling things. It was over the mountain and a long way down on the other side. Here they stopped while it was yet light, and there we staid all night. I can remember nothing about that night, except that I was very tired, and lay down on the ground and cried till I was asleep.

"The next day we set out and traveled many days in the woods before we came to a village of Indians. When we stopped at night the Indians would cut down a few boughs of hemlock on which to sleep, and then make up a great fire of logs at their feet, which lasted all night.

"When they cooked anything they stuck a stick in it and held it to the fire as long as they chose. They drank at the brooks and springs, and for me they made a little cup of white birch bark, out of which I drank. I can only remember that they staid several days at this first village, but where it was I have no recollection.

"After they had been here some days, very early one morning two of the same Indians took a horse and placed the boy and me upon it, and again set out on their journey. One went before on foot and the other behind, driving the horse. In this way we traveled a long way till we came to a village where these Indians belonged.

"I now found that one of them was a Delaware chief by the name of Tuck Horse. This was a great Delaware name, but I do not know its meaning. We were kept here some days, when they came and took away the boy, and I never saw him again, and do not know what became of him.

"Early one morning this Tuck Horse came and took me, and dressed my hair in the Indian way, and then painted my face and skin. He then dressed me in beautiful wampum beads, and made me look, as I thought, very fine. I was much pleased with the beautiful wampum.

"We then lived on a hill, and I remember he took me by the hand and led me down to the river side to a house, where lived an old man and woman. They had once several children, but now they were all gone—either killed in battle, or having died very young. When the Indians thus lose all their children they often adopt some new child as their own, and treat it in all respects like their own. This is the reason why they so often carry away the children of white people.

"I was brought to these old people to have them adopt me, if they would. They seemed unwilling at first, but after Tuck Horse had talked with them awhile, they agreed to it, and this was my home. They gave me the name of We-let-a-wash, which was the name of their youngest child whom they had lately buried. It had now got to be the fall of the year (1779), for chestnuts had come.

"The Indians were very numerous here, and here we remained all the following winter. The Indians were in the service of the British, and were furnished by them with provisions. They seemed to be the gathered remnants of several nations of Indians. I remember that there was a fort here.

"In the spring I went with the parents who had adopted me, to Sandusky, where we spent the next summer; but in the fall we returned again to the fort—the place where I was made an Indian child—and here we spent the second winter, (1780).

"In the next spring we went down to a large river, which is Detroit River, where we stopped and built a great number of bark canoes. I might have said before, that there was war between the British and the Americans, and that the American army had driven the Indians around the fort where I was adopted. In their fights I remember the Indians used to take and bring home scalps, but I do not know how many.

"When our canoes were all done we went up Detroit River, where we remained about three years. I think peace had now been made between the British and Americans, and so we lived by hunting, fishing, and raising corn...

"The reason why we staid here so long was, that we heard that the Americans had destroyed all our villages and corn fields. After these years my family and another Delaware family removed to Ke-ki-ong-a (now Fort Wayne). I don't know where the other Indians went.

"This was now our home, and I suppose we lived here as many as twenty-six or thirty years. I was there long after I was full grown, and I was there at the time of Harmar's defeat. At the time this battle was fought the women and children were all made to run north. I cannot remember whether the Indians took any prisoners, or brought home any scalps at this time. After the battle they all scattered to their various homes, as was their custom, till gathered again for some particular object. I then returned again to Ke-ki-ong-a. The Indians who returned from this battle were Delawares, Pottawatamies, Shawnese and Miamis.

"I was always treated well and kindly; and while I lived with them I was married to a Delaware. He afterwards left me and the country, and went west of the Mississippi. The Delawares and Miamis were then all living together.

"I was afterwards married to a Miami, a chief, and a deaf man. His name was She-pan-can-ah. After being married to him I had four children—two boys and two girls. My boys both died while young. The girls are living and are here in this room at the present time.

"I cannot recollect much about the Indian wars with the whites, which were so common and so bloody. I well remember a battle and a defeat of the Americans at Fort Washington, which is now Cincinnati. I remember how Wayne, or ' Mad Anthony,' drove the Indians away and built the fort.

"The Indians then scattered all over the country, and lived upon game, which was very abundant. After this they encamped all along on Eel River. After peace was made we all returned to Fort Wayne and received provisions from the Americans, and there I lived a long time.

"I had removed with my family to the Mississinewa River some time before the battle of Tippecanoe. The Indians who fought in that battle were the Kickapoos, Pottawatamies and Shawnese. The Miamis were not there. I heard of the battle on the Mississinewa, but my husband was a deaf man, and never went to the wars, and I did not know much about them."

George Winter 1810-1876 Francis Slocum

At the conclusion of this account of her capture, life and wanderings with the Indians for so many years, there was a pause for a few minutes. Every one present seemed deeply impressed with the story and the simple, artless manner in which it was related. In a short time the conversation was resumed, "We live where our father and mother used to live, on the banks of the beautiful Susquehanna, and we want you to return with us; we will give you of our property, and you shall be one of us and share all that we have. You shall have a good house and everything you desire. Oh, do go back with us!"

George Winter 1810-1876 Francis Slocum and daughter

"No, I cannot," was the sad but firm reply. " I have always lived with the Indians; they have always used me very kindly; I am used to them. The Great Spirit has always allowed me to live with them, and I wish to live and die with them.

"Your wah-puh-mone [looking glass] may be longer than mine, but this is my home. I do not wish to live any better, or anywhere else, and I think the Great Spirit has permitted me to live so long because I have always lived with the Indians. I should have died sooner if I had left them.

"My husband and my boys are buried here, and I cannot leave them. On his dying day my husband charged me not to leave the Indians. I have a house and large lands, two daughters, a son-in-law, three grand-children, and everything to make me comfortable; why should I go and be like a fish out of water?"

When her birth family could not convince her to leave the village, the Slocum family hired George Winter to paint a portrait of Frances & her daughter. Winter wrote descriptions of her family in his journals. The artist wrote of Frances in 1839, "Frances Slocum's face bore the marks of deep-seated lines. The muscles of her cheeks were like corded rises, and her forehead ran in almost right angular lines. There was indication of no unwanted cares upon her countenance beyond time's influence which peculiarly marks the decline of life...She bore the impress of old age, without its extreme feebleness. Her hair which was evidently of dark brown color was now frosted. Though bearing some resemblance to her family, yet her cheek bones seemed to bear the Indian characteristic in that particular - face broad, nose somewhat bulby, mouth perhaps indicating some degree of severity. In her ears she wore some few ear bobs."

Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst:University of Massachusetts Press, 2001)

Susan Sleeper-Smith, Enduring Nations: Native Americans in the Midwest, ed. R. David Edmunds (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008)

John F Meginnes, Women in America from Colonial Times to the 20th Century: Biography of Frances Slocum (New York: Arno Press, 1891, reprint 1974)

Stewart Rafert, The Miami Indians of Indiana: A Persistent People 1654-1994 (Indiana Historical Society, 1996)

James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985)

Jim J. Buss, "They Found and Left Her an Indian: Gender, Race, and the Whitening of Young Bear." Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Jun 01, 2008; Vol. 29, No. 2/3, p. 1-35.

"Winter's Description of Francis [sic]Slocum," Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History 1:3 (1905)

Friday, December 28, 2018

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Two Chippewyan Warriors and a Woman

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Poweshiek (1791–1854) - Meskwaki chief

Poweshiek (1791–1854) by Thomas Burnell Colbert

Poweshiek (1791–1854) was a Meskwaki chief, the son of Black Thunder and a member of the Bear clan of the Meskwaki (Fox) tribe. His name has been translated variously as "to dash the water off," "he who shakes [something] off [himself]," and "roused bear."

A large man who perhaps weighed more than 250 pounds, Poweshiek was known both for his warlike nature and for his kindness while reportedly leading his followers with an "iron hand."Along with chief Wapello, Poweshiek lived near the present-day city of Davenport on the Mississippi River, where he and his followers had intermingled with their allies the Sauk, who had left Illinois for Iowa in the late 1820s. In 1832, when Sauk chief Black Hawk led his followers back into Illinois and precipitated the so-called Black Hawk War, Poweshiek did much to keep the Meskwaki out of the conflict, just as Keokuk did among the remaining Sauk. Poweshiek was one of the signers of the treaty of 1832 that ended the Black Hawk War and transferred land in Iowa–territory that the Meskwaki thought belonged to them, not the Sauk—to the United States.

With the end of the Black Hawk War, the U.S. government designated Keokuk as principal chief of a confederated Sauk and Meskwaki tribe designated as the Sac and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi. Thereafter, Poweshiek began to lose influence to Keokuk. Nonetheless, he held stature as a leader of the Meskwaki. He was among the signers of the treaty of 1836 that sold the Keokuk Reserve to the United States. In 1837 he was a member of the entourage led by Keokuk that traveled to Washington, D.C., to treat with their Sioux enemies over disputed territory. There he signed a treaty selling even more land to the United States. After the party of treaty makers toured eastern cities, Poweshiek returned to Iowa and moved his village away from along the Iowa River (near Iowa City) westward to near a site near Des Moines.

Poweshiek broke with Keokuk in 1840 over the distribution of annuity funds. Along with Sauk chiefs Keokuk and Appanoose and Meskwaki chief Wapello, Poweshiek was one of the so-called money chiefs who paid the debts their tribesmen owed white traders. However, Poweshiek and others believed that agent John Beach favored Keokuk when giving out the monies.

Poweshiek was the main Meskwaki chief to sign the treaty of 1842 (Wapello had died), in which Keokuk, responding to debt, poverty, and government pressure as well as bribes to tribal leaders, agreed to sell the remaining Sauk and Meskwaki land in Iowa to the United States. However, Poweshiek did so reluctantly, for he and many of his people did not want to remove to Kansas. In fact, while encamped with 40 lodges and over 400 people for two years in southern Iowa, Poweshiek and his band of Meskwaki twice returned to their old village site only to be re-removed.

In 1845 Keokuk led the Sauk and Meskwaki out of Iowa to Kansas—that is, except those Meskwaki who returned to their former tribal grounds. Most in Poweshiek's band had not left Iowa. In Kansas, Poweshiek took the lead in trying to end Meskwaki tribal ties with the Sauk. The Meskwaki wanted to be an independent tribe, receive their own annuities, and be allowed to legally return to Iowa. Poweshiek died before the Meskwaki received permission to return to Iowa and ultimately to be paid their share of tribal annuities.

Poweshiek was not considered a gifted orator or diplomat, as was Keokuk. Rather, observers described him as brave, blunt, and respected. He was known for keeping his word and desiring that justice prevail in controversies. He became a prominent chief among the Meskwaki, and according to missionary Cutting Marsh, before removal Poweshiek was "very much beloved" by his band. However, as a result of removal from Iowa, many blamed Poweshiek for that unhappy occurrence, even though he endeavored to obtain the changes they desired after removal. And like some of his fellow Meskwaki and Sauk, he indulged heavily in alcohol. Although many whites called Poweshiek the "peaceful Indian" because he did not fight against them and signed several treaties, he had no desire to acculturate to white ways, nor was he a pacifist. In response to a request to establish a school for his people, Poweshiek famously replied, "We do not want to learn; we want to kill Sioux."

Sources include F. R. Aumann, "Poweshiek," Palimpsest 8 (1927), 297–305; Michael D. Green, "'We Dance in Opposite Directions': Mesquakie (Fox) Separation from the Sac and Fox Tribe," Ethnohistory 30 (1983), 129–40; William J. Petersen, The Story of Iowa, vol. 1 (1952); Henry Sabin and Edwin L. Sabin, The Making of Iowa (1900); and Thomas L. McKinney and James Hall, Bio graphical Sketches and Anecdotes of Ninety-five of 120 Principal Chiefs from Indian Tribes of North America, vol. 1 (1838). The most complete tribal history is William T. Hagan, The Sac and Fox Indians (1958).

This research from Colbert, Thomas Burnell. "Poweshiek" The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, 2009.

Poweshiek (1791–1854) was a Meskwaki chief, the son of Black Thunder and a member of the Bear clan of the Meskwaki (Fox) tribe. His name has been translated variously as "to dash the water off," "he who shakes [something] off [himself]," and "roused bear."

A large man who perhaps weighed more than 250 pounds, Poweshiek was known both for his warlike nature and for his kindness while reportedly leading his followers with an "iron hand."Along with chief Wapello, Poweshiek lived near the present-day city of Davenport on the Mississippi River, where he and his followers had intermingled with their allies the Sauk, who had left Illinois for Iowa in the late 1820s. In 1832, when Sauk chief Black Hawk led his followers back into Illinois and precipitated the so-called Black Hawk War, Poweshiek did much to keep the Meskwaki out of the conflict, just as Keokuk did among the remaining Sauk. Poweshiek was one of the signers of the treaty of 1832 that ended the Black Hawk War and transferred land in Iowa–territory that the Meskwaki thought belonged to them, not the Sauk—to the United States.

With the end of the Black Hawk War, the U.S. government designated Keokuk as principal chief of a confederated Sauk and Meskwaki tribe designated as the Sac and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi. Thereafter, Poweshiek began to lose influence to Keokuk. Nonetheless, he held stature as a leader of the Meskwaki. He was among the signers of the treaty of 1836 that sold the Keokuk Reserve to the United States. In 1837 he was a member of the entourage led by Keokuk that traveled to Washington, D.C., to treat with their Sioux enemies over disputed territory. There he signed a treaty selling even more land to the United States. After the party of treaty makers toured eastern cities, Poweshiek returned to Iowa and moved his village away from along the Iowa River (near Iowa City) westward to near a site near Des Moines.

Poweshiek broke with Keokuk in 1840 over the distribution of annuity funds. Along with Sauk chiefs Keokuk and Appanoose and Meskwaki chief Wapello, Poweshiek was one of the so-called money chiefs who paid the debts their tribesmen owed white traders. However, Poweshiek and others believed that agent John Beach favored Keokuk when giving out the monies.

Poweshiek was the main Meskwaki chief to sign the treaty of 1842 (Wapello had died), in which Keokuk, responding to debt, poverty, and government pressure as well as bribes to tribal leaders, agreed to sell the remaining Sauk and Meskwaki land in Iowa to the United States. However, Poweshiek did so reluctantly, for he and many of his people did not want to remove to Kansas. In fact, while encamped with 40 lodges and over 400 people for two years in southern Iowa, Poweshiek and his band of Meskwaki twice returned to their old village site only to be re-removed.

In 1845 Keokuk led the Sauk and Meskwaki out of Iowa to Kansas—that is, except those Meskwaki who returned to their former tribal grounds. Most in Poweshiek's band had not left Iowa. In Kansas, Poweshiek took the lead in trying to end Meskwaki tribal ties with the Sauk. The Meskwaki wanted to be an independent tribe, receive their own annuities, and be allowed to legally return to Iowa. Poweshiek died before the Meskwaki received permission to return to Iowa and ultimately to be paid their share of tribal annuities.

Poweshiek was not considered a gifted orator or diplomat, as was Keokuk. Rather, observers described him as brave, blunt, and respected. He was known for keeping his word and desiring that justice prevail in controversies. He became a prominent chief among the Meskwaki, and according to missionary Cutting Marsh, before removal Poweshiek was "very much beloved" by his band. However, as a result of removal from Iowa, many blamed Poweshiek for that unhappy occurrence, even though he endeavored to obtain the changes they desired after removal. And like some of his fellow Meskwaki and Sauk, he indulged heavily in alcohol. Although many whites called Poweshiek the "peaceful Indian" because he did not fight against them and signed several treaties, he had no desire to acculturate to white ways, nor was he a pacifist. In response to a request to establish a school for his people, Poweshiek famously replied, "We do not want to learn; we want to kill Sioux."

Sources include F. R. Aumann, "Poweshiek," Palimpsest 8 (1927), 297–305; Michael D. Green, "'We Dance in Opposite Directions': Mesquakie (Fox) Separation from the Sac and Fox Tribe," Ethnohistory 30 (1983), 129–40; William J. Petersen, The Story of Iowa, vol. 1 (1952); Henry Sabin and Edwin L. Sabin, The Making of Iowa (1900); and Thomas L. McKinney and James Hall, Bio graphical Sketches and Anecdotes of Ninety-five of 120 Principal Chiefs from Indian Tribes of North America, vol. 1 (1838). The most complete tribal history is William T. Hagan, The Sac and Fox Indians (1958).

This research from Colbert, Thomas Burnell. "Poweshiek" The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, 2009.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

18C Indigenous Women in Latin American Families - Caste Paintings - Racial Mixes Determined Status, Privileges, & Obligations

1763 Caste Painting Series by Miguel Cabrera (c 1695-1768) De Español y Mulata; Morisca

Status in the social hierarchy of much of the 18C Middle & South Americas status depended on skin color & intermarriages between social groups.

There was an exhibit in New York City, "New World Orders: Casta Painting & Colonial Latin America" at the Americas Society in 1996.

And then, a couple of years ago, I read that the curator of that exhibit Ilona Katzew's book called Casta Painting: Images of Race in 18th-Century Mexico. It was published by the Yale University Press, in New Haven in 2004, and focused on the paintings of Miguel Cabrera c 1695-1768.

Katzew used this primary source to help explain the need for the caste system in Mexico. In 1770 Francisco Antonio Lorenzana, a Spanish prelate and archbishop of Mexico from 1766 to 1772, remarked on the diversity of Mexico's population as opposed to Spain's: "Two worlds God has placed in the hands of our Catholic Monarch, and the New does not resemble the Old, not in its climate, its customs, nor its inhabitants; it has another legislative body, another council for governing, yet always with the end of making them alike: In the Old Spain only a single caste of men is recognized, in the New many and different."

Colonial Mexico was home to a vast array of ethnoracial groups. In the first years following the Spanish conquest, most people fell into one of 3 distinct ethnoracial categories. They were either indigenous Nahuas, peninsular Spaniards, or Africans (both enslaved and free). Sexual contact between Spaniards, Indians, & Blacks occurred from the 16th-century on, resulting in a growing group of racially-mixed people known collectively as castas-a term used by Spaniards & creoles (Spaniards born in the Americas) to distinguish themselves from racially-mixed people. By the end of the 18th century, about 1/4 of the population of Mexico was racially mixed.

A series of depictions of families called casta paintings emerged as a way of illustrating the proper classification of the various mixing of races that determined rank in that society. For historians, they are a treasure trove of costumes & home settings & even shops & employments. But they are much more than that.

1763 Caste Painting Series by Miguel Cabrera (c 1695-1768) De Español y Torna atrás; Tente en el aire

Maria Elena Martinex's Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford University Press, 2008) based on her 2002 PhD dissertation at the Univeristy of Chicago, is a fine in-depth study of the interplay between the Spanish concept of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) & colonial Mexico's sistema de castas, a hierarchical system of social classification based primarily on ancestry. She examines how this notion surfaced amid socio-religious tensions in early modern Spain, & was initially used against Jewish & Muslim converts to Christianity. It was then exported to the Americas, adapted to colonial conditions, & employed to create & reproduce identity categories according to descent. Martínez also examines how the state, church, Inquisition, & other institutions in colonial Mexico used the notion of purity of blood over time to shape the region's patriotic & racial ideologies.

In these family scenes, husbands & wives from different races are shown with their offspring & ranked according to their place in Mexico's social structure.

These paintings were very popular in 18C Spain as well as other parts of Europe. Peru & the French colonies also classified society according to racial mixes.

In colonial Latin America the racial caste system was so overt that a baby's social identity as white, indigenous, African, or mixed was officially assigned in the church baptismal register.

According to the European racial notions of the day in Spain, "purity of blood" was considered a virtue; consequently, Africans and Indians are nobly rendered.

Mixed-race couples depicted in these paintings are clearly poorer, wearing shabbier clothes in starker circumstances, than their purer-blooded ancestors. Spaniards & their Indian or African brides sport rich European costumes, while Lobo- Mestizo couples wear plain or even ragged dress.

Europeans did not regard these casta paintings as art objects but as proof of their wealth & power & as insturctive ethnographic illustrations.

These casta paintings were depictions by the colonial intruder trying to establish a means of retaing power using New World gene pools that were quickly merging.

Colonial powers assigned different castes with different privileges & obligations. These visual representations made it easy for all to understand, whether they could read or not.

"Casta" is Spanish for caste. These "casta paintings" are incredibly frank documents of the race-based social hierarchy that existed in colonial Latin America during the 17th & 18th century.

On the other hand, however, these paintings also depict a rather harmonious coexistence of Indian, Spaniard & Black, in 18th-century Mexico.

Some of the terms denoting the mix of races had zoological meanings.The lowest among the mixes of races were often denigrated with animal names like Lobo (Wolf) & Coyote.

As the mixing further dilutes the pure gene pools, negative terms such as “Tente en el aire” meaning "throw in the air" suggest something that is worth nothing.

Many of the names/terms used to describe the identity of an individuals racial heritage within the casta paintings were made up of common slang terms. Some of these terms are still in use today, mulatto is has the widest usage.

Mexican Castes:

Albarazado = Cambujo + Mulatto

Albino/Ochavado = Spanish + African or Morisco

Allí te estás = Chamizo + Mestiza

Barcino = Albarazado + Mutlata

Barnocino = Albarazado + Mestiza

Calpamulato = Zambaigo + Loba

Cambujo = Zambaigo + Indian

Cambur = African, Spanish, + Indian

Cambuto/a = Spanish + African

Castizo = Spanish + Mestizo (Spanish & a person 1/2 Spanish & 1/2 indigenous)

Chamizo = Coyote + Indian

Chino or Albino = Spanish + Morisca

Cimarrón = African, Spanish, + Indian

Coyote = African, Spanish, + Indian

Coyote = Indian + Metiza

Jíbaro/Jabaro = Lobo + China /Spanish, Indian, or African

Lobo = Indian, African + Salta atrás

Mestizo = Spanish + Indian

Morisco or Cuarterón = Spanish + Mulatto

Mulato = Spanish + African

Negro fino = African + Spanish

No te entiendo = Tente en el aire + Mulatta

Nometoques = Parts of many races, including African

Pardo = Spanish, Indian, + African

Prieto = African + Spanish

Salta atrás/Tornatras = Spanish, African, + Albina

Sambahigo = Cambujo + Indian or Spanish or African

Spanish = Castiza + Spanish

Tente en el aire = Calpamulatto + Cambuja

Torna atrás = No te entiendo + Indian

Tresalvo = Spanish + African

Zambaigo = Lobo + Indian

Zambo = Indian + African

Castes in Peru:

Mestizo = Spaniard + Indian,

Quadroon, Quinterón = Spaniard + Mestiza or Mulatto

Mulatto = Spaniard + Black,

Quinterona, Requinterona = Spaniard + Mulatto,

Requinterona = Spaniard + Mulatto,

Cholo = Mestizo + Indian,

Chinese = Mulatto + Indian,

Chinese Quadroon = Spaniard + Chinese,

Zambo = Black + Indian, or Black + Mulatto

French Colonial castes:

Sacatra = Griffe + Black,

Griffe = Black + Mulatto

Marabon = Mulatto + Griffe,

Mulatto = White + Black,

Quarteron = White + Mulatto,

Metif = White + Quarteron,

Meamelouc = White + Metif,

Quarteron = White + Meamelouc,

Sang-mele = White + Quarteron

Hierarchy of the Casta Paintings Miguel Cabrera, 1763

1. De Español y d’India; Mestisa

2. De Español y Mestiza, Castiza

3. De Español y Castiza, Español

4. De Español y Negra, Mulata

5. De Español y Mulata; Morisca

6. De Español y Morisca; Albina

7. De Español y Albina; Torna atrás

8. De Español y Torna atrás; Tente en el aire

9. De Negro y d’India, China cambuja.

10. De Chino cambujo y d’India; Loba

11. De Lobo y d’India, Albarazado

12. De Albarazado y Mestiza, Barcino

13 De Indio y Barcina; Zambuigua

14. De Castizo y Mestiza; Chamizo

15. De Mestizo y d’India; Coyote

16. Indios gentiles (Heathen Indians)

Although the artists creating many of the paintings in this post are unidentified, painters commissioned to work in this genre included Juan Rodriguez Juarez, Miguel Cabrera, Jose de Paex, Jose Alfaro, Ignacio Maria Barreda, Andres de Islas, Mariano Guerrero, Luis Berruecco, Ignacio de Castro, Jose de Bustos, and Jose Joaquin Magon.

There was an exhibit in New York City, "New World Orders: Casta Painting & Colonial Latin America" at the Americas Society in 1996.

Shown there were intimate, family portrayals of the racial mixing of the melting pot of the Americas forged from New World colonialism & Spanish Catholicism. Generally Latin America is defined as the region of the Americas where Romance languages (i.e., those derived from Latin) – particularly Spanish and Portuguese, & variably French – are primarily spoken.

And then, a couple of years ago, I read that the curator of that exhibit Ilona Katzew's book called Casta Painting: Images of Race in 18th-Century Mexico. It was published by the Yale University Press, in New Haven in 2004, and focused on the paintings of Miguel Cabrera c 1695-1768.

Katzew used this primary source to help explain the need for the caste system in Mexico. In 1770 Francisco Antonio Lorenzana, a Spanish prelate and archbishop of Mexico from 1766 to 1772, remarked on the diversity of Mexico's population as opposed to Spain's: "Two worlds God has placed in the hands of our Catholic Monarch, and the New does not resemble the Old, not in its climate, its customs, nor its inhabitants; it has another legislative body, another council for governing, yet always with the end of making them alike: In the Old Spain only a single caste of men is recognized, in the New many and different."

Colonial Mexico was home to a vast array of ethnoracial groups. In the first years following the Spanish conquest, most people fell into one of 3 distinct ethnoracial categories. They were either indigenous Nahuas, peninsular Spaniards, or Africans (both enslaved and free). Sexual contact between Spaniards, Indians, & Blacks occurred from the 16th-century on, resulting in a growing group of racially-mixed people known collectively as castas-a term used by Spaniards & creoles (Spaniards born in the Americas) to distinguish themselves from racially-mixed people. By the end of the 18th century, about 1/4 of the population of Mexico was racially mixed.

A series of depictions of families called casta paintings emerged as a way of illustrating the proper classification of the various mixing of races that determined rank in that society. For historians, they are a treasure trove of costumes & home settings & even shops & employments. But they are much more than that.

1763 Caste Painting Series by Miguel Cabrera (c 1695-1768) De Español y Torna atrás; Tente en el aire

Maria Elena Martinex's Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford University Press, 2008) based on her 2002 PhD dissertation at the Univeristy of Chicago, is a fine in-depth study of the interplay between the Spanish concept of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) & colonial Mexico's sistema de castas, a hierarchical system of social classification based primarily on ancestry. She examines how this notion surfaced amid socio-religious tensions in early modern Spain, & was initially used against Jewish & Muslim converts to Christianity. It was then exported to the Americas, adapted to colonial conditions, & employed to create & reproduce identity categories according to descent. Martínez also examines how the state, church, Inquisition, & other institutions in colonial Mexico used the notion of purity of blood over time to shape the region's patriotic & racial ideologies.

In these family scenes, husbands & wives from different races are shown with their offspring & ranked according to their place in Mexico's social structure.

These paintings were very popular in 18C Spain as well as other parts of Europe. Peru & the French colonies also classified society according to racial mixes.

In colonial Latin America the racial caste system was so overt that a baby's social identity as white, indigenous, African, or mixed was officially assigned in the church baptismal register.

According to the European racial notions of the day in Spain, "purity of blood" was considered a virtue; consequently, Africans and Indians are nobly rendered.

Mixed-race couples depicted in these paintings are clearly poorer, wearing shabbier clothes in starker circumstances, than their purer-blooded ancestors. Spaniards & their Indian or African brides sport rich European costumes, while Lobo- Mestizo couples wear plain or even ragged dress.

re commissioned by on-site colonial administrative & religious officials in the 1700s, often meant to serve as instructive souvenirs to be sent back to Spain. Because these paintings were a form of propaganda & social control generated by the colonial elite, it is impossible to tell from their content how these subordinate groups of people understood, accomodated, or resisted the process of domination by the colonial administrations.

Europeans did not regard these casta paintings as art objects but as proof of their wealth & power & as insturctive ethnographic illustrations.

These casta paintings were depictions by the colonial intruder trying to establish a means of retaing power using New World gene pools that were quickly merging.

Colonial powers assigned different castes with different privileges & obligations. These visual representations made it easy for all to understand, whether they could read or not.

"Casta" is Spanish for caste. These "casta paintings" are incredibly frank documents of the race-based social hierarchy that existed in colonial Latin America during the 17th & 18th century.

On the other hand, however, these paintings also depict a rather harmonious coexistence of Indian, Spaniard & Black, in 18th-century Mexico.

Some of the terms denoting the mix of races had zoological meanings.The lowest among the mixes of races were often denigrated with animal names like Lobo (Wolf) & Coyote.

As the mixing further dilutes the pure gene pools, negative terms such as “Tente en el aire” meaning "throw in the air" suggest something that is worth nothing.

Many of the names/terms used to describe the identity of an individuals racial heritage within the casta paintings were made up of common slang terms. Some of these terms are still in use today, mulatto is has the widest usage.

Mexican Castes:

Albarazado = Cambujo + Mulatto

Albino/Ochavado = Spanish + African or Morisco

Allí te estás = Chamizo + Mestiza

Barcino = Albarazado + Mutlata

Barnocino = Albarazado + Mestiza

Calpamulato = Zambaigo + Loba

Cambujo = Zambaigo + Indian

Cambur = African, Spanish, + Indian

Cambuto/a = Spanish + African

Castizo = Spanish + Mestizo (Spanish & a person 1/2 Spanish & 1/2 indigenous)

Chamizo = Coyote + Indian

Chino or Albino = Spanish + Morisca

Cimarrón = African, Spanish, + Indian

Coyote = African, Spanish, + Indian

Coyote = Indian + Metiza

Jíbaro/Jabaro = Lobo + China /Spanish, Indian, or African

Lobo = Indian, African + Salta atrás

Mestizo = Spanish + Indian

Morisco or Cuarterón = Spanish + Mulatto

Mulato = Spanish + African

Negro fino = African + Spanish

No te entiendo = Tente en el aire + Mulatta

Nometoques = Parts of many races, including African

Pardo = Spanish, Indian, + African

Prieto = African + Spanish

Salta atrás/Tornatras = Spanish, African, + Albina

Sambahigo = Cambujo + Indian or Spanish or African

Spanish = Castiza + Spanish

Tente en el aire = Calpamulatto + Cambuja

Torna atrás = No te entiendo + Indian

Tresalvo = Spanish + African

Zambaigo = Lobo + Indian

Zambo = Indian + African

Castes in Peru:

Mestizo = Spaniard + Indian,

Quadroon, Quinterón = Spaniard + Mestiza or Mulatto

Mulatto = Spaniard + Black,

Quinterona, Requinterona = Spaniard + Mulatto,

Requinterona = Spaniard + Mulatto,

Cholo = Mestizo + Indian,

Chinese = Mulatto + Indian,

Chinese Quadroon = Spaniard + Chinese,

Zambo = Black + Indian, or Black + Mulatto

French Colonial castes:

Sacatra = Griffe + Black,

Griffe = Black + Mulatto

Marabon = Mulatto + Griffe,

Mulatto = White + Black,

Quarteron = White + Mulatto,

Metif = White + Quarteron,

Meamelouc = White + Metif,

Quarteron = White + Meamelouc,

Sang-mele = White + Quarteron

Hierarchy of the Casta Paintings Miguel Cabrera, 1763

1. De Español y d’India; Mestisa

2. De Español y Mestiza, Castiza

3. De Español y Castiza, Español

4. De Español y Negra, Mulata

5. De Español y Mulata; Morisca

6. De Español y Morisca; Albina

7. De Español y Albina; Torna atrás

8. De Español y Torna atrás; Tente en el aire

9. De Negro y d’India, China cambuja.

10. De Chino cambujo y d’India; Loba

11. De Lobo y d’India, Albarazado

12. De Albarazado y Mestiza, Barcino

13 De Indio y Barcina; Zambuigua

14. De Castizo y Mestiza; Chamizo

15. De Mestizo y d’India; Coyote

16. Indios gentiles (Heathen Indians)

Although the artists creating many of the paintings in this post are unidentified, painters commissioned to work in this genre included Juan Rodriguez Juarez, Miguel Cabrera, Jose de Paex, Jose Alfaro, Ignacio Maria Barreda, Andres de Islas, Mariano Guerrero, Luis Berruecco, Ignacio de Castro, Jose de Bustos, and Jose Joaquin Magon.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)