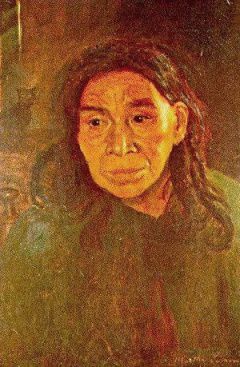

Cassilly Adams (American artist, 1843-1921) On the Run

A descendant of President John Adams, Kassilli or Cassilly Adams (1843-1921) was born in Zanesville, Ohio. His father, William Adams, was an amateur painter. Young Cassilly studied painting at the Academy of Art in Boston and Cincinnati Art School. During the Civil War he served in the US Navy. From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries. By 1880, Adams was living in St. Louis. In 1884, the artist created a monumental canvas depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn (death of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army and its famous commander George Custer) - "Custer's Last Fight." The painting was exhibited across the country, and then was purchased by the company "Anheuser-Busch" and later donated to the Seventh Cavalry. After the restoration of the original during the Great Depression, it was exhibited in the officers' club at Fort Bliss (Texas), and June 13, 1946 was burned in a fire. Despite the success of "Custer's Last Fight," Adams remained a relatively unknown artist. He focused on the image of Indians American West Plains life, worked as an illustrator, a farmer. He died Kassilli Adams May 8, 1921 in Traders Point near Indianapolis.

Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Sunday, April 28, 2019

American artist Seth Eastman (1808-1875) portrays Native Americans

Seth Eastman (American artist, 1808-1875) Striking the Post Preparing for Counting Coup

Counting Coup played an extremely important part in the life of a Great Plains warrior. The above picture depicts American Indians striking the coup post during practise sessions. Counting coup refers to the winning of prestige against an enemy by the Plains Indians of North America. Warriors won prestige by acts of bravery in the face of the enemy, which could be recorded in various ways & retold as stories. Any blow struck against the enemy counted as a coup, but the most prestigious acts included touching an enemy warrior with the hand, bow, or coup stick & escaping unharmed. Touching the first enemy to die in battle or touching the enemy's defensive works also counted as coup. Counting coup could also involve stealing an enemy's weapons or horses tied up to his lodge in camp. Risk of injury or death was required to count coup. Escaping unharmed while counting coup was considered a higher honor than being wounded in the attempt. A warrior who won coup was permitted to wear an eagle feather in his hair. If he had been wounded in the attempt, however, he was required to paint the feather red to indicate this. After a battle or exploit, the people of a tribe would gather together to recount their acts of bravery & "count coup." Coups were recorded by putting notches in a coup stick. Indians of the Pacific Northwest would tie an eagle feather to their coup stick for each coup counted, but many tribes did not do so. Among the Blackfoot tribe of the upper Missouri River Valley, coup could be recorded by the placement of "coup bars" on the sleeves & shoulders of special shirts that bore paintings of the warrior's exploits in battle. Many shirts of this sort have survived to the present, including some in European museums.

Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Seth Eastman (1808-1875) found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the US Military Academy at West Point, where officers-in-training were taught basic drawing & drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin & Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. --- While at Fort Snelling, Eastman married Wakaninajinwin (Stands Sacred), the 15-year-old daughter of Cloud Man, Dakota chief. Eastman left in 1832, for another military assignment soon after the birth of their baby girl, Winona, & he declared his marriage ended when he left. Winona was also known as Mary Nancy Eastman & was the mother of Charles Alexander Eastman, author of Indian Boyhood. --- From 1833 to 1840, Eastman taught drawing at West Point. In 1835, he married his 2nd wife & was reassigned to Fort Snelling as a military commander & remained there with Mary & their 5 children for the next 7 years. During this time Eastman began recording the everyday way of life of the Dakota & the Ojibwa people. Transferred to posts in Florida, & Texas in the 1840s, Eastman made sketches of the native peoples there. This experience prepared him for the next 5 yeas in Washington, DC, where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs & illustrated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's important 6-volume Historical Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, & Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. In 1867, Eastman returned to the Capitol to paint a series of scenes of Native American life for the House Committee on Indian Affairs. From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & 1875. Of his 17 paintings of forts, 8 are located in the Senate, while the others are displayed on the House side of the Capitol. Eastman was working on the painting West Point, when he died in 1875.

Counting Coup played an extremely important part in the life of a Great Plains warrior. The above picture depicts American Indians striking the coup post during practise sessions. Counting coup refers to the winning of prestige against an enemy by the Plains Indians of North America. Warriors won prestige by acts of bravery in the face of the enemy, which could be recorded in various ways & retold as stories. Any blow struck against the enemy counted as a coup, but the most prestigious acts included touching an enemy warrior with the hand, bow, or coup stick & escaping unharmed. Touching the first enemy to die in battle or touching the enemy's defensive works also counted as coup. Counting coup could also involve stealing an enemy's weapons or horses tied up to his lodge in camp. Risk of injury or death was required to count coup. Escaping unharmed while counting coup was considered a higher honor than being wounded in the attempt. A warrior who won coup was permitted to wear an eagle feather in his hair. If he had been wounded in the attempt, however, he was required to paint the feather red to indicate this. After a battle or exploit, the people of a tribe would gather together to recount their acts of bravery & "count coup." Coups were recorded by putting notches in a coup stick. Indians of the Pacific Northwest would tie an eagle feather to their coup stick for each coup counted, but many tribes did not do so. Among the Blackfoot tribe of the upper Missouri River Valley, coup could be recorded by the placement of "coup bars" on the sleeves & shoulders of special shirts that bore paintings of the warrior's exploits in battle. Many shirts of this sort have survived to the present, including some in European museums.

Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Seth Eastman (1808-1875) found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the US Military Academy at West Point, where officers-in-training were taught basic drawing & drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin & Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. --- While at Fort Snelling, Eastman married Wakaninajinwin (Stands Sacred), the 15-year-old daughter of Cloud Man, Dakota chief. Eastman left in 1832, for another military assignment soon after the birth of their baby girl, Winona, & he declared his marriage ended when he left. Winona was also known as Mary Nancy Eastman & was the mother of Charles Alexander Eastman, author of Indian Boyhood. --- From 1833 to 1840, Eastman taught drawing at West Point. In 1835, he married his 2nd wife & was reassigned to Fort Snelling as a military commander & remained there with Mary & their 5 children for the next 7 years. During this time Eastman began recording the everyday way of life of the Dakota & the Ojibwa people. Transferred to posts in Florida, & Texas in the 1840s, Eastman made sketches of the native peoples there. This experience prepared him for the next 5 yeas in Washington, DC, where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs & illustrated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's important 6-volume Historical Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, & Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. In 1867, Eastman returned to the Capitol to paint a series of scenes of Native American life for the House Committee on Indian Affairs. From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & 1875. Of his 17 paintings of forts, 8 are located in the Senate, while the others are displayed on the House side of the Capitol. Eastman was working on the painting West Point, when he died in 1875.

Friday, April 26, 2019

American artist Seth Eastman (1808-1875) portrays a Winnebago Encampment

Seth Eastman (American artist, 1808-1875) Winnebago Encampment

From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries. The Hoocąągra, sometimes called "Ho-Chunk" or Wisconsin Winnebago, are a Siouan Native American group native to the present-day states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, & parts of Iowa & Illinois. The written history of the Ho-Chunk begins with the records made from the reports of Jean Nicolet, who, in 1634, was the first European to establish contact with this people. At that time, the Winnebago/Ho-Chunk occupied the area around Green Bay of Lake Michigan in Wisconsin, reaching beyond Lake Winnebago to the Wisconsin River & to the Rock River in Illinois. The tribe traditionally practiced corn agriculture in addition to hunting. They were not advanced in agriculture. Living on Green Bay, they fished, collected wild rice, gathered sugar from maple trees, & hunted game.

Although their language indicates common origin with the other peoples of this language group, who originated in the East, the oral traditions of the Ho-Chunk speak of no other homeland other than what is now large portions of Wisconsin, Iowa, & Minnesota. These traditions suggest that they were a very populous people & the dominant group in Wisconsin in the century before Nicolet's visit. While their language was Hoocąąk, their culture was similar to the Algonquian peoples. Current elders suggest that their pre-history is connected to the mound builders of the region of the Hopewell period.

The oral history also indicates that in the mid-16C, the influx of Ojibwa peoples in the northern portion of their range caused the Ho-Chunk to move to the south of their territory. They had some friction with the Illiniwek, as well as a division of the people: the Chiwere group (Iowa, Missouri, Ponca, & Oto tribes) moved west because the reduced range made it difficult for such a large population to be sustained.

Jean Nicolet (1598-1642) was noted for discovering & exploring Lake Michigan, Mackinac Island, Green Bay, & for being the 1st European to step foot in what is now the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Nicolet reported a gathering of approximately 5,000 warriors as the Ho-Chunk entertained him. Historians estimate that the population in 1634 may have ranged from 8,000 to more than 20,000. Between that time & the return of French trappers & traders in the late 1650s, the population was reduced drastically. Later reports were that the Ho-Chunk numbered only about 500 people. They lost their dominance in the region. When numerous Algonquian tribes migrated west to escape the problems caused by the powerful Iroquois tribes' aggressiveness in the Beaver Wars, they competed with the Ho-Chunk for game & resources, who had to yield to their greater numbers.

The reasons given by historians for the reduction in population vary, but they agree on three major causes: the loss of several hundred warriors in a storm on a lake, infectious disease epidemics after contact with Europeans, & attacks by the Illiniwek.

The warriors were said to be lost on Lake Michigan after they had repulsed the first attack by invading the Potawatomi from what is now Door County, Wisconsin. Another says the number was 600. Another claim is that the 500 were lost in a storm on Lake Winnebago during a failed campaign against the Meskwaki, while yet another says it was in a battle against the Sauk.

Even with such a serious loss of warriors, the historian R. David Edmunds notes that it was not enough to cause the near elimination of an entire people. He suggests 2 additional causes. The Winnebago apparently suffered from a widespread disease, perhaps an epidemic of one of the European infectious diseases. They had no immunity to the new diseases & suffered high rates of fatalities. Ho-Chunk accounts said the victims turned yellow, which is not a trait of smallpox, however. Historians have rated disease as the major reason for the losses in all American Indian populations.

Edmunds notes as a third cause of losses the following historic account: that many of the Ho-Chunk's traditional enemies, the Illiniwek, came to help the tribe at their time of suffering & famine, aggravated by the loss of their hunters. The Winnebago reportedly attacked the Illiniwek & ate the dead. Enraged, additional Illiniwek warriors retaliated & killed nearly all the Winnebago.

After peace was established between the French & Iroquois in 1701, many of the Algonquian peoples returned to their homelands to the east. The Ho-Chunk were relieved of the pressure on their territory. After 1741, while some remained in the Green Bay area, most returned inland. From a low of perhaps less than 500, the population of the people gradually recovered, aided by intermarriage with neighboring tribes, & with some of the French traders & trappers. A count from 1736 gives a population of 700. In 1806, they numbered 2,900 or more. A census in 1846 reported 4,400, but in 1848 the number given is only 2,500. Like other American Indian tribes, the Ho-Chunk suffered great losses during the smallpox epidemics of 1757–58 & 1836. In the 19th-century epidemic, they lost nearly one-quarter of their population. Today the total population of the Ho-Chunk people is about 12,000.

Through a series of forced moves imposed by the U.S. government in the 19C, the tribe was relocated to reservations increasingly further west: in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota & finally Nebraska. Through the period of forced re-locations, many tribe members returned to previous homes, especially in Wisconsin, despite the US Army's repeated roundups & removals. The U.S. government finally allowed the Wisconsin Winnebago to homestead land in the state, where they have achieved federal recognition as a tribe. The Ho-Chunk in Nebraska have gained independent federal recognition as a tribe & have a reservation in Thurston County. Waukon & Decorah, county seats of Allamakee & Winneshiek County, Iowa, respectively, were named after the 19C Ho-Chunk chief Waukon Decorah.

From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & amp; 1875. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Seth Eastman (1808-1875) found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the US Military Academy at West Point, where officers-in-training were taught basic drawing & drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin & Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. --- While at Fort Snelling, Eastman married Wakaninajinwin (Stands Sacred), the 15-year-old daughter of Cloud Man, Dakota chief. Eastman left in 1832, for another military assignment soon after the birth of their baby girl, Winona, & he declared his marriage ended when he left. Winona was also known as Mary Nancy Eastman & was the mother of Charles Alexander Eastman, author of Indian Boyhood. --- From 1833 to 1840, Eastman taught drawing at West Point. In 1835, he married his 2nd wife & was reassigned to Fort Snelling as a military commander & remained there with Mary & their 5 children for the next 7 years. During this time Eastman began recording the everyday way of life of the Dakota & the Ojibwa people. Transferred to posts in Florida, & Texas in the 1840s, Eastman made sketches of the native peoples there. This experience prepared him for the next 5 yeas in Washington, DC, where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs & illustrated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's important 6-volume Historical Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, & Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. In 1867, Eastman returned to the Capitol to paint a series of scenes of Native American life for the House Committee on Indian Affairs. From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & 1875. Of his 17 paintings of forts, 8 are located in the Senate, while the others are displayed on the House side of the Capitol. Eastman was working on the painting West Point, when he died in 1875.

From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries. The Hoocąągra, sometimes called "Ho-Chunk" or Wisconsin Winnebago, are a Siouan Native American group native to the present-day states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, & parts of Iowa & Illinois. The written history of the Ho-Chunk begins with the records made from the reports of Jean Nicolet, who, in 1634, was the first European to establish contact with this people. At that time, the Winnebago/Ho-Chunk occupied the area around Green Bay of Lake Michigan in Wisconsin, reaching beyond Lake Winnebago to the Wisconsin River & to the Rock River in Illinois. The tribe traditionally practiced corn agriculture in addition to hunting. They were not advanced in agriculture. Living on Green Bay, they fished, collected wild rice, gathered sugar from maple trees, & hunted game.

Although their language indicates common origin with the other peoples of this language group, who originated in the East, the oral traditions of the Ho-Chunk speak of no other homeland other than what is now large portions of Wisconsin, Iowa, & Minnesota. These traditions suggest that they were a very populous people & the dominant group in Wisconsin in the century before Nicolet's visit. While their language was Hoocąąk, their culture was similar to the Algonquian peoples. Current elders suggest that their pre-history is connected to the mound builders of the region of the Hopewell period.

The oral history also indicates that in the mid-16C, the influx of Ojibwa peoples in the northern portion of their range caused the Ho-Chunk to move to the south of their territory. They had some friction with the Illiniwek, as well as a division of the people: the Chiwere group (Iowa, Missouri, Ponca, & Oto tribes) moved west because the reduced range made it difficult for such a large population to be sustained.

Jean Nicolet (1598-1642) was noted for discovering & exploring Lake Michigan, Mackinac Island, Green Bay, & for being the 1st European to step foot in what is now the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Nicolet reported a gathering of approximately 5,000 warriors as the Ho-Chunk entertained him. Historians estimate that the population in 1634 may have ranged from 8,000 to more than 20,000. Between that time & the return of French trappers & traders in the late 1650s, the population was reduced drastically. Later reports were that the Ho-Chunk numbered only about 500 people. They lost their dominance in the region. When numerous Algonquian tribes migrated west to escape the problems caused by the powerful Iroquois tribes' aggressiveness in the Beaver Wars, they competed with the Ho-Chunk for game & resources, who had to yield to their greater numbers.

The reasons given by historians for the reduction in population vary, but they agree on three major causes: the loss of several hundred warriors in a storm on a lake, infectious disease epidemics after contact with Europeans, & attacks by the Illiniwek.

The warriors were said to be lost on Lake Michigan after they had repulsed the first attack by invading the Potawatomi from what is now Door County, Wisconsin. Another says the number was 600. Another claim is that the 500 were lost in a storm on Lake Winnebago during a failed campaign against the Meskwaki, while yet another says it was in a battle against the Sauk.

Even with such a serious loss of warriors, the historian R. David Edmunds notes that it was not enough to cause the near elimination of an entire people. He suggests 2 additional causes. The Winnebago apparently suffered from a widespread disease, perhaps an epidemic of one of the European infectious diseases. They had no immunity to the new diseases & suffered high rates of fatalities. Ho-Chunk accounts said the victims turned yellow, which is not a trait of smallpox, however. Historians have rated disease as the major reason for the losses in all American Indian populations.

Edmunds notes as a third cause of losses the following historic account: that many of the Ho-Chunk's traditional enemies, the Illiniwek, came to help the tribe at their time of suffering & famine, aggravated by the loss of their hunters. The Winnebago reportedly attacked the Illiniwek & ate the dead. Enraged, additional Illiniwek warriors retaliated & killed nearly all the Winnebago.

After peace was established between the French & Iroquois in 1701, many of the Algonquian peoples returned to their homelands to the east. The Ho-Chunk were relieved of the pressure on their territory. After 1741, while some remained in the Green Bay area, most returned inland. From a low of perhaps less than 500, the population of the people gradually recovered, aided by intermarriage with neighboring tribes, & with some of the French traders & trappers. A count from 1736 gives a population of 700. In 1806, they numbered 2,900 or more. A census in 1846 reported 4,400, but in 1848 the number given is only 2,500. Like other American Indian tribes, the Ho-Chunk suffered great losses during the smallpox epidemics of 1757–58 & 1836. In the 19th-century epidemic, they lost nearly one-quarter of their population. Today the total population of the Ho-Chunk people is about 12,000.

Through a series of forced moves imposed by the U.S. government in the 19C, the tribe was relocated to reservations increasingly further west: in Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota & finally Nebraska. Through the period of forced re-locations, many tribe members returned to previous homes, especially in Wisconsin, despite the US Army's repeated roundups & removals. The U.S. government finally allowed the Wisconsin Winnebago to homestead land in the state, where they have achieved federal recognition as a tribe. The Ho-Chunk in Nebraska have gained independent federal recognition as a tribe & have a reservation in Thurston County. Waukon & Decorah, county seats of Allamakee & Winneshiek County, Iowa, respectively, were named after the 19C Ho-Chunk chief Waukon Decorah.

From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & amp; 1875. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Seth Eastman (1808-1875) found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the US Military Academy at West Point, where officers-in-training were taught basic drawing & drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin & Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. --- While at Fort Snelling, Eastman married Wakaninajinwin (Stands Sacred), the 15-year-old daughter of Cloud Man, Dakota chief. Eastman left in 1832, for another military assignment soon after the birth of their baby girl, Winona, & he declared his marriage ended when he left. Winona was also known as Mary Nancy Eastman & was the mother of Charles Alexander Eastman, author of Indian Boyhood. --- From 1833 to 1840, Eastman taught drawing at West Point. In 1835, he married his 2nd wife & was reassigned to Fort Snelling as a military commander & remained there with Mary & their 5 children for the next 7 years. During this time Eastman began recording the everyday way of life of the Dakota & the Ojibwa people. Transferred to posts in Florida, & Texas in the 1840s, Eastman made sketches of the native peoples there. This experience prepared him for the next 5 yeas in Washington, DC, where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs & illustrated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft's important 6-volume Historical Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, & Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. In 1867, Eastman returned to the Capitol to paint a series of scenes of Native American life for the House Committee on Indian Affairs. From the office of the United States Senate curator, we learn that in 1870, the House Committee on Military Affairs commissioned artist Seth Eastman 17 to paint images of important fortifications in the United States. He completed the works between 1870 & 1875. Of his 17 paintings of forts, 8 are located in the Senate, while the others are displayed on the House side of the Capitol. Eastman was working on the painting West Point, when he died in 1875.

Wednesday, April 24, 2019

Indian Scout by Cassilly Adams (1843-1921)

Cassilly Adams (American artist, 1843-1921) Indian Scout

Native Americans have made up an integral part of U.S. military conflicts since America's beginning. Colonists recruited Indian allies during such instances as the Pequot War from 1634–1638, the Revolutionary War, as well as in War of 1812. Native Americans also fought on both sides during the American Civil War, as well as military missions abroad including the most notable, the Codetalkers who served in World War II. The Scouts were active in the American West in the late 19C & early 20C. Including those who accompanied General John J. Pershing in 1916 on his expedition to Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Indian Scouts were officially deactivated in 1947 when their last member retired from the Army at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. For many Indians it was an important form of interaction with white American culture & their 1st major encounter with the whites’ way of thinking & doing things. Information from the U.S. Army Center for Military History.

A descendant of President John Adams, Kassilli or Cassilly Adams (1843-1921) was born in Zanesville, Ohio. His father, William Adams, was an amateur painter. Young Cassilly studied painting at the Academy of Art in Boston and Cincinnati Art School. During the Civil War he served in the US Navy. By 1880, Adams was living in St. Louis. In 1884, the artist created a monumental canvas depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn (death of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army and its famous commander George Custer) - "Custer's Last Fight." The painting was exhibited across the country, and then was purchased by the company "Anheuser-Busch" and later donated to the Seventh Cavalry. After the restoration of the original during the Great Depression, it was exhibited in the officers' club at Fort Bliss (Texas), and June 13, 1946 was burned in a fire. Despite the success of "Custer's Last Fight," Adams remained a relatively unknown artist. He focused on the image of Indians American West Plains life, worked as an illustrator, a farmer. He died Kassilli Adams May 8, 1921 in Traders Point near Indianapolis.

Native Americans have made up an integral part of U.S. military conflicts since America's beginning. Colonists recruited Indian allies during such instances as the Pequot War from 1634–1638, the Revolutionary War, as well as in War of 1812. Native Americans also fought on both sides during the American Civil War, as well as military missions abroad including the most notable, the Codetalkers who served in World War II. The Scouts were active in the American West in the late 19C & early 20C. Including those who accompanied General John J. Pershing in 1916 on his expedition to Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Indian Scouts were officially deactivated in 1947 when their last member retired from the Army at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. For many Indians it was an important form of interaction with white American culture & their 1st major encounter with the whites’ way of thinking & doing things. Information from the U.S. Army Center for Military History.

A descendant of President John Adams, Kassilli or Cassilly Adams (1843-1921) was born in Zanesville, Ohio. His father, William Adams, was an amateur painter. Young Cassilly studied painting at the Academy of Art in Boston and Cincinnati Art School. During the Civil War he served in the US Navy. By 1880, Adams was living in St. Louis. In 1884, the artist created a monumental canvas depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn (death of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army and its famous commander George Custer) - "Custer's Last Fight." The painting was exhibited across the country, and then was purchased by the company "Anheuser-Busch" and later donated to the Seventh Cavalry. After the restoration of the original during the Great Depression, it was exhibited in the officers' club at Fort Bliss (Texas), and June 13, 1946 was burned in a fire. Despite the success of "Custer's Last Fight," Adams remained a relatively unknown artist. He focused on the image of Indians American West Plains life, worked as an illustrator, a farmer. He died Kassilli Adams May 8, 1921 in Traders Point near Indianapolis.

Monday, April 22, 2019

Buffalo Hunt attributed to Karl Ferdinand Wimar (1828-1862)

Attributed to Karl Ferdinand Wimar (1828-1862 a painter of the American West was also known as Charles Wimar & Carl Wimar) Buffalo Hunt

Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed: The Transcontinental Railroad connected East & West—& accelerated the destruction of what had been in the center of North America

By Gilbert King, Smithsonian.com, July 17, 2012

"The telegram arrived in New York from Promontory Summit, Utah, at 3:05 p.m. on May 10, 1869, announcing one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the century: The last rail is laid; the last spike driven; the Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1086 miles west of the Missouri river & 690 miles east of Sacramento City.

"The telegram was signed, “Leland Stanford, Central Pacific Railroad. T. P. Durant, Sidney Dillon, John Duff, Union Pacific Railroad,” & trumpeted news of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. After more than 6 years of backbreaking labor, east officially met west with the driving of a ceremonial golden spike. In City Hall Park in Manhattan, the announcement was greeted with the firing of 100 guns. Bells were rung across the country, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. Business was suspended in Chicago as people rushed to the streets, celebrating to the sounding of steam whistles & cannons booming.

"Not long after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, railroad financier George Francis Train proclaimed, “The great Pacific Railway is commenced.… Immigration will soon pour into these valleys. Ten millions of emigrants will settle in this golden land in twenty years.… This is the grandest enterprise under God!” Yet while Train may have envisioned all the glory & the possibilities of linking the East & the West coasts by “a strong band of iron,” he could not imagine the full & tragic impact of the Transcontinental Railroad, nor the speed at which it changed the shape of the American West. For in its wake, the lives of countless Native Americans were destroyed, & tens of millions of buffalo, which had roamed freely upon the Great Plains since the last ice age 10,000 years ago, were nearly driven to extinction in a massive slaughter made possible by the railroad.

"Following the Civil War, after deadly European diseases & hundreds of wars with the white man had already wiped out untold numbers of Native Americans, the U.S. government had ratified nearly 400 treaties with the Plains Indians. But as the Gold Rush, the pressures of Manifest Destiny, & land grants for railroad construction led to greater expansion in the West, the majority of these treaties were broken. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s first postwar command (Military Division of the Mississippi) covered the territory west of the Mississippi & east of the Rocky Mountains, & his top priority was to protect the construction of the railroads. In 1867, he wrote to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, “we are not going to let thieving, ragged Indians check & stop the progress” of the railroads. Outraged by the Battle of the Hundred Slain, where Lakota & Cheyenne warriors ambushed a troop of the U.S. Cavalry in Wyoming, scalping & mutilating the bodies of all 81 soldiers & officers, Sherman told Grant the year before, “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women & children.” When Grant assumed the presidency in 1869, he appointed Sherman Commanding General of the Army, & Sherman was responsible for U.S. engagement in the Indian Wars. On the ground in the West, Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan, assuming Sherman’s command, took to his task much as he had done in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, when he ordered the “scorched earth” tactics that presaged Sherman’s March to the Sea.

"Early on, Sheridan bemoaned a lack of troops: “No other nation in the world would have attempted reduction of these wild tribes & occupation of their country with less than 60,000 to 70,000 men, while the whole force employed & scattered over the enormous region…never numbered more than 14,000 men. The consequence was that every engagement was a forlorn hope.”

"The Army’s troops were well equipped for fighting against conventional enemies, but the guerrilla tactics of the Plains tribes confounded them at every turn. As the railways expanded, they allowed the rapid transport of troops & supplies to areas where battles were being waged. Sheridan was soon able to mount the kind of offensive he desired. In the Winter Campaign of 1868-69 against Cheyenne encampments, Sheridan set about destroying the Indians’ food, shelter & livestock with overwhelming force, leaving women & children at the mercy of the Army & Indian warriors little choice but to surrender or risk starvation. In one such surprise raid at dawn during a November snowstorm in Indian Territory, Sheridan ordered the nearly 700 men of the Seventh Cavalry, commanded by George Armstrong Custer, to “destroy villages & ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, & to bring back all women & children.” Custer’s men charged into a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, cutting down the Indians as they fled from lodges. Women & children were taken as hostages as part of Custer’s strategy to use them as human shields, but Cavalry scouts reported seeing women & children pursued & killed “without mercy” in what became known as the Washita Massacre. Custer later reported more than 100 Indian deaths, including that of Chief Black Kettle & his wife, Medicine Woman Later, shot in the back as they attempted to ride away on a pony. Cheyenne estimates of Indian deaths in the raid were about half of Custer’s total, & the Cheyenne did manage to kill 21 Cavalry troops while defending the attack. “If a village is attacked & women & children killed,” Sheridan once remarked, “the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack.”

"The Transcontinental Railroad made Sheridan’s strategy of “total war” much more effective. In the mid-19th century, it was estimated that 30 milion to 60 million buffalo roamed the plains. In massive & majestic herds, they rumbled by the hundreds of thousands, creating the sound that earned them the nickname “Thunder of the Plains.” The bison’s lifespan of 25 years, rapid reproduction & resiliency in their environment enabled the species to flourish, as Native Americans were careful not to overhunt, & even men like William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was hired by the Kansas Pacific Railroad to hunt the bison to feed thousands of rail laborers for years, could not make much of a dent in the buffalo population. In mid-century, trappers who had depleted the beaver populations of the Midwest began trading in buffalo robes & tongues; an estimated 200,000 buffalo were killed annually. Then the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad accelerated the decimation of the species.

"Massive hunting parties began to arrive in the West by train, with thousands of men packing .50 caliber rifles, & leaving a trail of buffalo carnage in their wake. Unlike the Native Americans or Buffalo Bill, who killed for food, clothing & shelter, the hunters from the East killed mostly for sport. Native Americans looked on with horror as landscapes & prairies were littered with rotting buffalo carcasses. The railroads began to advertise excursions for “hunting by rail,” where trains encountered massive herds alongside or crossing the tracks. Hundreds of men aboard the trains climbed to the roofs & took aim, or fired from their windows, leaving countless 1,500-pound animals where they died.

Harper’s Weekly described these hunting excursions: "Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; & a most interesting & exciting scene is the result. The train is “slowed” to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, & open from the windows & platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

"Hunters began killing buffalo by the hundreds of thousands in the winter months. One hunter, Orlando Brown brought down nearly 6,000 buffalo by himself & lost hearing in one ear from the constant firing of his .50 caliber rifle. The Texas legislature, sensing the buffalo were in danger of being wiped out, proposed a bill to protect the species. General Sheridan opposed it, stating, ”These men have done more in the last two years, & will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder & lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin & sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

"The devastation of the buffalo population signaled the end of the Indian Wars, & Native Americans were pushed into reservations. In 1869, the Comanche chief Tosawi was reported to have told Sheridan, “Me Tosawi. Me good Indian,” & Sheridan allegedly replied, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” The phrase was later misquoted, with Sheridan supposedly stating, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Sheridan denied he had ever said such a thing.

"By the end of the 19th century, only 300 buffalo were left in the wild. Congress finally took action, outlawing the killing of any birds or animals in Yellowstone National Park, where the only surviving buffalo herd could be protected. Conservationists established more wildlife preserves, & the species slowly rebounded. Today, there are more than 200,000 bison in North America.

"Sheridan acknowledged the role of the railroad in changing the face of the American West, & in his Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army in 1878, he acknowledged that the Native Americans were scuttled to reservations with no compensation beyond the promise of religious instruction & basic supplies of food & clothing—promises, he wrote, which were never fulfilled.

“We took away their country & their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease & decay among them, & it was for this & against this they made war. Could any one expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

See

Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army to the Secretary of War, The Year 1878, Washington Government Printing Office, 1878.

Robert G. Angevine, The Railroad & the State: War, Politics & Technology in Nineteenth-Century America, Stanford University Press 2004.

John D. McDermott, A Guide to the Indian Wars of the West, University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Ballard C. Campbell, Disasters, Accidents, & Crises in American History: A Reference Guide to the Nation’s Most Catastrophic Events, Facts on File, Inc., 2008.

Bobby Bridger, Buffalo Bill & Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West, University of Texas Press, 2002.

Paul Andrew Hutton, Phil Sheridan & His Army, University of Nebraska Press 1985.

A People & a Nation: A History of the United States Since 1865, Vol. 2, Wadsworth, 2010.

Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed: The Transcontinental Railroad connected East & West—& accelerated the destruction of what had been in the center of North America

By Gilbert King, Smithsonian.com, July 17, 2012

"The telegram arrived in New York from Promontory Summit, Utah, at 3:05 p.m. on May 10, 1869, announcing one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of the century: The last rail is laid; the last spike driven; the Pacific Railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1086 miles west of the Missouri river & 690 miles east of Sacramento City.

"The telegram was signed, “Leland Stanford, Central Pacific Railroad. T. P. Durant, Sidney Dillon, John Duff, Union Pacific Railroad,” & trumpeted news of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. After more than 6 years of backbreaking labor, east officially met west with the driving of a ceremonial golden spike. In City Hall Park in Manhattan, the announcement was greeted with the firing of 100 guns. Bells were rung across the country, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. Business was suspended in Chicago as people rushed to the streets, celebrating to the sounding of steam whistles & cannons booming.

"Not long after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, railroad financier George Francis Train proclaimed, “The great Pacific Railway is commenced.… Immigration will soon pour into these valleys. Ten millions of emigrants will settle in this golden land in twenty years.… This is the grandest enterprise under God!” Yet while Train may have envisioned all the glory & the possibilities of linking the East & the West coasts by “a strong band of iron,” he could not imagine the full & tragic impact of the Transcontinental Railroad, nor the speed at which it changed the shape of the American West. For in its wake, the lives of countless Native Americans were destroyed, & tens of millions of buffalo, which had roamed freely upon the Great Plains since the last ice age 10,000 years ago, were nearly driven to extinction in a massive slaughter made possible by the railroad.

"Following the Civil War, after deadly European diseases & hundreds of wars with the white man had already wiped out untold numbers of Native Americans, the U.S. government had ratified nearly 400 treaties with the Plains Indians. But as the Gold Rush, the pressures of Manifest Destiny, & land grants for railroad construction led to greater expansion in the West, the majority of these treaties were broken. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s first postwar command (Military Division of the Mississippi) covered the territory west of the Mississippi & east of the Rocky Mountains, & his top priority was to protect the construction of the railroads. In 1867, he wrote to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, “we are not going to let thieving, ragged Indians check & stop the progress” of the railroads. Outraged by the Battle of the Hundred Slain, where Lakota & Cheyenne warriors ambushed a troop of the U.S. Cavalry in Wyoming, scalping & mutilating the bodies of all 81 soldiers & officers, Sherman told Grant the year before, “we must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women & children.” When Grant assumed the presidency in 1869, he appointed Sherman Commanding General of the Army, & Sherman was responsible for U.S. engagement in the Indian Wars. On the ground in the West, Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan, assuming Sherman’s command, took to his task much as he had done in the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, when he ordered the “scorched earth” tactics that presaged Sherman’s March to the Sea.

"Early on, Sheridan bemoaned a lack of troops: “No other nation in the world would have attempted reduction of these wild tribes & occupation of their country with less than 60,000 to 70,000 men, while the whole force employed & scattered over the enormous region…never numbered more than 14,000 men. The consequence was that every engagement was a forlorn hope.”

"The Army’s troops were well equipped for fighting against conventional enemies, but the guerrilla tactics of the Plains tribes confounded them at every turn. As the railways expanded, they allowed the rapid transport of troops & supplies to areas where battles were being waged. Sheridan was soon able to mount the kind of offensive he desired. In the Winter Campaign of 1868-69 against Cheyenne encampments, Sheridan set about destroying the Indians’ food, shelter & livestock with overwhelming force, leaving women & children at the mercy of the Army & Indian warriors little choice but to surrender or risk starvation. In one such surprise raid at dawn during a November snowstorm in Indian Territory, Sheridan ordered the nearly 700 men of the Seventh Cavalry, commanded by George Armstrong Custer, to “destroy villages & ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, & to bring back all women & children.” Custer’s men charged into a Cheyenne village on the Washita River, cutting down the Indians as they fled from lodges. Women & children were taken as hostages as part of Custer’s strategy to use them as human shields, but Cavalry scouts reported seeing women & children pursued & killed “without mercy” in what became known as the Washita Massacre. Custer later reported more than 100 Indian deaths, including that of Chief Black Kettle & his wife, Medicine Woman Later, shot in the back as they attempted to ride away on a pony. Cheyenne estimates of Indian deaths in the raid were about half of Custer’s total, & the Cheyenne did manage to kill 21 Cavalry troops while defending the attack. “If a village is attacked & women & children killed,” Sheridan once remarked, “the responsibility is not with the soldiers but with the people whose crimes necessitated the attack.”

"The Transcontinental Railroad made Sheridan’s strategy of “total war” much more effective. In the mid-19th century, it was estimated that 30 milion to 60 million buffalo roamed the plains. In massive & majestic herds, they rumbled by the hundreds of thousands, creating the sound that earned them the nickname “Thunder of the Plains.” The bison’s lifespan of 25 years, rapid reproduction & resiliency in their environment enabled the species to flourish, as Native Americans were careful not to overhunt, & even men like William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was hired by the Kansas Pacific Railroad to hunt the bison to feed thousands of rail laborers for years, could not make much of a dent in the buffalo population. In mid-century, trappers who had depleted the beaver populations of the Midwest began trading in buffalo robes & tongues; an estimated 200,000 buffalo were killed annually. Then the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad accelerated the decimation of the species.

"Massive hunting parties began to arrive in the West by train, with thousands of men packing .50 caliber rifles, & leaving a trail of buffalo carnage in their wake. Unlike the Native Americans or Buffalo Bill, who killed for food, clothing & shelter, the hunters from the East killed mostly for sport. Native Americans looked on with horror as landscapes & prairies were littered with rotting buffalo carcasses. The railroads began to advertise excursions for “hunting by rail,” where trains encountered massive herds alongside or crossing the tracks. Hundreds of men aboard the trains climbed to the roofs & took aim, or fired from their windows, leaving countless 1,500-pound animals where they died.

Harper’s Weekly described these hunting excursions: "Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; & a most interesting & exciting scene is the result. The train is “slowed” to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, & open from the windows & platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

"Hunters began killing buffalo by the hundreds of thousands in the winter months. One hunter, Orlando Brown brought down nearly 6,000 buffalo by himself & lost hearing in one ear from the constant firing of his .50 caliber rifle. The Texas legislature, sensing the buffalo were in danger of being wiped out, proposed a bill to protect the species. General Sheridan opposed it, stating, ”These men have done more in the last two years, & will do more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the entire regular army has done in the last forty years. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder & lead, if you will; but for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin & sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle.”

"The devastation of the buffalo population signaled the end of the Indian Wars, & Native Americans were pushed into reservations. In 1869, the Comanche chief Tosawi was reported to have told Sheridan, “Me Tosawi. Me good Indian,” & Sheridan allegedly replied, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” The phrase was later misquoted, with Sheridan supposedly stating, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Sheridan denied he had ever said such a thing.

"By the end of the 19th century, only 300 buffalo were left in the wild. Congress finally took action, outlawing the killing of any birds or animals in Yellowstone National Park, where the only surviving buffalo herd could be protected. Conservationists established more wildlife preserves, & the species slowly rebounded. Today, there are more than 200,000 bison in North America.

"Sheridan acknowledged the role of the railroad in changing the face of the American West, & in his Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army in 1878, he acknowledged that the Native Americans were scuttled to reservations with no compensation beyond the promise of religious instruction & basic supplies of food & clothing—promises, he wrote, which were never fulfilled.

“We took away their country & their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease & decay among them, & it was for this & against this they made war. Could any one expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

See

Annual Report of the General of the U.S. Army to the Secretary of War, The Year 1878, Washington Government Printing Office, 1878.

Robert G. Angevine, The Railroad & the State: War, Politics & Technology in Nineteenth-Century America, Stanford University Press 2004.

John D. McDermott, A Guide to the Indian Wars of the West, University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Ballard C. Campbell, Disasters, Accidents, & Crises in American History: A Reference Guide to the Nation’s Most Catastrophic Events, Facts on File, Inc., 2008.

Bobby Bridger, Buffalo Bill & Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West, University of Texas Press, 2002.

Paul Andrew Hutton, Phil Sheridan & His Army, University of Nebraska Press 1985.

A People & a Nation: A History of the United States Since 1865, Vol. 2, Wadsworth, 2010.

Sunday, April 21, 2019

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Mandan War Chief with His Favorite Wife

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Mandan War Chief with His Favorite Wife

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived primarily for centuries in what is now North Dakota. The Mandan historically lived along the banks of the Missouri River & its tributaries—the Heart & Knife Rivers—in present-day North & South Dakota. Speakers of Mandan, a Siouan language, developed a settled, agrarian culture. They established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges, some 40 feet in diameter, surrounding a central plaza. The Mandan traded corn surpluses with other tribes in exchange for bison meat. They established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges, some 40 feet (12 m) in diameter, surrounding a central plaza. The Mandan were divided into bands. The bands all practiced extensive farming, which was carried out by the women, including the drying & processing of corn. The Mandan-Hidatsa settlements, called the "Marketplace of the Central Plains" were major hubs of trade in the Great Plains Indian trading networks. Crops were exchanged, along with other goods that traveled from as far as the Pacific Northwest Coast. Investigation of their sites on the northern Plains have revealed items traceable as well to the Tennessee River, Florida, the Gulf Coast, & the Atlantic Seaboard.

The Mandan gradually moved upriver, & consolidated in present-day North Dakota by the 15C. From 1500 to about 1782, the Mandan reached their apogee of population & influence. Their villages showed increasing densities as well as stronger fortifications, for instance at Huff Village. It had 115 large lodges with more than 1,000 residents.

The bands did not often move along the river until the late 18th century, after their populations plummeted due to smallpox & other epidemics.The Mandan were a great trading nation, trading especially their large corn surpluses with other tribes in exchange for bison meat & fat. Food was the primary item, but they also traded for horses, guns, & other trade goods.

The Koatiouak, mentioned in a 1736 letter by Jesuit Jean-Pierre Aulneau, are identified as Mandans. Aulneau was killed before his planned expedition to visit the Mandans could take place. The known first European known to visit the Mandan was the French Canadian trader Sieur de la Verendrye in 1738. The Mandans carried him into their village, whose location is unknown.It is estimated that at the time of his visit, 15,000 Mandan resided in the nine well-fortified villages on the Heart River; some villages had as many as 1,000 lodges. According to Vérendrye, the Mandans at that time were a large, powerful, prosperous nation who were able to dictate trade on their own terms. They traded with other Native Americans both from the north & the south, from downriver.

Horses were acquired by the Mandan in the mid-18C from the Apache to the South. The Mandan used them both for transportation, to carry packs & pull travois, & for hunting. The horses helped with the expansion of Mandan hunting territory on to the Plains. The encounter with the French from Canada in the 18th century created a trading link between the French & Native Americans of the region; the Mandan served as middlemen in the trade in furs, horses, guns, crops & buffalo products. Spanish merchants & officials in St. Louis (after France had ceded its territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain in 1763) explored the Missouri & strengthened relations with the Mandan (whom they called Mandanas). They wanted to discourage trade in the region by the English & the Americans, but the Mandan carried on open trade with all competitors.

A smallpox epidemic broke out in Mexico City in 1779/1780. It slowly spread northward through the Spanish empire, by trade & warfare, reaching the northern plains in 1781. The Comanche & Shoshone had become infected & carried the disease throughout their territory. Other warring & trading peoples also became infected. The Mandan lost so many people that the number of clans was reduced from thirteen to seven; three clan names from villages west of the Missouri were lost altogether. They eventually moved northward about 25 miles, & consolidated into two villages, one on each side of the river, as they rebuilt following the epidemic. Similarly afflicted, the much reduced Hidatsa people joined them for defense. Through & after the epidemic, they were raided by Lakota Sioux & Crow warriors.

In 1796 the Mandan were visited by the Welsh explorer John Evans, who was hoping to find proof that their language contained Welsh words. In July 1797 he wrote to Dr. Samuel Jones, "Thus having explored & charted the Missurie for 1,800 miles & by my Communications with the Indians this side of the Pacific Ocean from 35 to 49 degrees of Latitude, I am able to inform you that there is no such People as the Welsh Indians."British & French Canadians from the north carried out more than 20 fur-trading expeditions down to the Hidatsa & Mandan villages in the years 1794 to 1800.

By 1804 when Lewis & Clark visited the tribe, the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox epidemics & warring bands of Assiniboine, Lakota & Arikara. The nine villages had consolidated into two villages in the 1780s, one on each side of the Missouri. But they continued their famous hospitality, & the Lewis & Clark expedition stopped near their villages for the winter because of it. In honor of their hosts, the expedition dubbed the settlement they constructed Fort Mandan. It was here that Lewis & Clark first met Sacagawea, a captive Shoshone woman. Sacagawea accompanied the expedition as it traveled west, assisting them with information & translating skills as they journeyed toward the Pacific Ocean. Upon their return to the Mandan villages, Lewis & Clark took the Mandan Chief Sheheke (Coyote or Big White) with them to Washington to meet with President Thomas Jefferson. He returned to the upper Missouri. He had survived the smallpox epidemic of 1781, but in 1812 Chief Sheheke was killed in a battle with Hidatsa.

In 1825 the Mandans signed a peace treaty with the leaders of the Atkinson-O'Fallon Expedition. The treaty required that the Mandans recognize the supremacy of the United States, admit that they reside on United States territory, & relinquish all control & regulation of trade to the United States. The Mandan & the United States Army never met in open warfare.

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived primarily for centuries in what is now North Dakota. The Mandan historically lived along the banks of the Missouri River & its tributaries—the Heart & Knife Rivers—in present-day North & South Dakota. Speakers of Mandan, a Siouan language, developed a settled, agrarian culture. They established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges, some 40 feet in diameter, surrounding a central plaza. The Mandan traded corn surpluses with other tribes in exchange for bison meat. They established permanent villages featuring large, round, earth lodges, some 40 feet (12 m) in diameter, surrounding a central plaza. The Mandan were divided into bands. The bands all practiced extensive farming, which was carried out by the women, including the drying & processing of corn. The Mandan-Hidatsa settlements, called the "Marketplace of the Central Plains" were major hubs of trade in the Great Plains Indian trading networks. Crops were exchanged, along with other goods that traveled from as far as the Pacific Northwest Coast. Investigation of their sites on the northern Plains have revealed items traceable as well to the Tennessee River, Florida, the Gulf Coast, & the Atlantic Seaboard.

The Mandan gradually moved upriver, & consolidated in present-day North Dakota by the 15C. From 1500 to about 1782, the Mandan reached their apogee of population & influence. Their villages showed increasing densities as well as stronger fortifications, for instance at Huff Village. It had 115 large lodges with more than 1,000 residents.

The bands did not often move along the river until the late 18th century, after their populations plummeted due to smallpox & other epidemics.The Mandan were a great trading nation, trading especially their large corn surpluses with other tribes in exchange for bison meat & fat. Food was the primary item, but they also traded for horses, guns, & other trade goods.

The Koatiouak, mentioned in a 1736 letter by Jesuit Jean-Pierre Aulneau, are identified as Mandans. Aulneau was killed before his planned expedition to visit the Mandans could take place. The known first European known to visit the Mandan was the French Canadian trader Sieur de la Verendrye in 1738. The Mandans carried him into their village, whose location is unknown.It is estimated that at the time of his visit, 15,000 Mandan resided in the nine well-fortified villages on the Heart River; some villages had as many as 1,000 lodges. According to Vérendrye, the Mandans at that time were a large, powerful, prosperous nation who were able to dictate trade on their own terms. They traded with other Native Americans both from the north & the south, from downriver.

Horses were acquired by the Mandan in the mid-18C from the Apache to the South. The Mandan used them both for transportation, to carry packs & pull travois, & for hunting. The horses helped with the expansion of Mandan hunting territory on to the Plains. The encounter with the French from Canada in the 18th century created a trading link between the French & Native Americans of the region; the Mandan served as middlemen in the trade in furs, horses, guns, crops & buffalo products. Spanish merchants & officials in St. Louis (after France had ceded its territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain in 1763) explored the Missouri & strengthened relations with the Mandan (whom they called Mandanas). They wanted to discourage trade in the region by the English & the Americans, but the Mandan carried on open trade with all competitors.

A smallpox epidemic broke out in Mexico City in 1779/1780. It slowly spread northward through the Spanish empire, by trade & warfare, reaching the northern plains in 1781. The Comanche & Shoshone had become infected & carried the disease throughout their territory. Other warring & trading peoples also became infected. The Mandan lost so many people that the number of clans was reduced from thirteen to seven; three clan names from villages west of the Missouri were lost altogether. They eventually moved northward about 25 miles, & consolidated into two villages, one on each side of the river, as they rebuilt following the epidemic. Similarly afflicted, the much reduced Hidatsa people joined them for defense. Through & after the epidemic, they were raided by Lakota Sioux & Crow warriors.

In 1796 the Mandan were visited by the Welsh explorer John Evans, who was hoping to find proof that their language contained Welsh words. In July 1797 he wrote to Dr. Samuel Jones, "Thus having explored & charted the Missurie for 1,800 miles & by my Communications with the Indians this side of the Pacific Ocean from 35 to 49 degrees of Latitude, I am able to inform you that there is no such People as the Welsh Indians."British & French Canadians from the north carried out more than 20 fur-trading expeditions down to the Hidatsa & Mandan villages in the years 1794 to 1800.

By 1804 when Lewis & Clark visited the tribe, the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox epidemics & warring bands of Assiniboine, Lakota & Arikara. The nine villages had consolidated into two villages in the 1780s, one on each side of the Missouri. But they continued their famous hospitality, & the Lewis & Clark expedition stopped near their villages for the winter because of it. In honor of their hosts, the expedition dubbed the settlement they constructed Fort Mandan. It was here that Lewis & Clark first met Sacagawea, a captive Shoshone woman. Sacagawea accompanied the expedition as it traveled west, assisting them with information & translating skills as they journeyed toward the Pacific Ocean. Upon their return to the Mandan villages, Lewis & Clark took the Mandan Chief Sheheke (Coyote or Big White) with them to Washington to meet with President Thomas Jefferson. He returned to the upper Missouri. He had survived the smallpox epidemic of 1781, but in 1812 Chief Sheheke was killed in a battle with Hidatsa.

In 1825 the Mandans signed a peace treaty with the leaders of the Atkinson-O'Fallon Expedition. The treaty required that the Mandans recognize the supremacy of the United States, admit that they reside on United States territory, & relinquish all control & regulation of trade to the United States. The Mandan & the United States Army never met in open warfare.

Saturday, April 20, 2019

An Indian Camp by Albert Bierstadt (German-born American painter, 1830-1902)

Matthew Biagell explains in his book Albert Bierstadt that,"Athough Bierstadt made probing studies of individual Indians during his travels in the West, he usually generalized their appearances & activities in his paintings. He placed them, as he placed European peasants in earlier works, in the middle distance, so that we witness their presence in a landscape setting rather than focus on their movements." Many of his landscapes including Native Americans are the western equivalent of his European generalized landscapes & reveals Bierstadt's consistent attitude toward subject matter regardless of its locale human subjects are engaged in seemingly unrelated activities. His paintings, bathed in a golden glow, often suggest nostalgia for a previous age when Native Americans were thought to have lived harmoniously with nature. Here they are not wily, wicked, or predatory, but are engaged instead in peaceful domestic industry. Works such as this are obviously part of the broad western European tradition of Arcadian scenes, but in its American version the tradition assumes a particular complexity & ambivalence. His painting including Natives often portray the nobility of the Indians before their contact with Europeans & subsequent debasement. Paintings displaying this attitude undoubtedly provided the public with the images it wanted to see, especially during the years Indians were systematically being driven from their lands. Suchromanticized paintings might also be considered retardataire; the Indian, noble or otherwise, no longer engaged many serious 19C writers after the 1850s, & precise anthropological & linguistic analyses of Indian tribes were already being included in the Pacific railroad reports by that time.

Albert Bierstadt (German-born American painter, 1830-1902) was best known for these lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West. To paint the scenes, Bierstadt joined several journeys of the Westward Expansion. Bierstadt, was born in Solingen, Germany. He was still a toddler, when his family moved from Germany to New Bedford in Massachusetts. In 1853, he returned to Germany to study in Dusseldorf, where he refined his technical abilities by painting Alpine landscapes. After he returned to America in 1857, he joined an overland survey expedition traveling westward across the country. Along the route, he took countless photographs & made sketches & returned East to paint from them. He exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum from 1859-1864, at the Brooklyn Art Association from 1861-1879, & at the Boston Art Club from 1873-1880. A member of the National Academy of Design from 1860-1902, he kept a studio in the 10th Street Studio Building, New York City from 1861-1879. He was a member of the Century Association from 1862-1902, when he died.

Friday, April 19, 2019

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Klatsop Indians

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Klatsop Indians

The Clatsop are a small tribe of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. In the early 19th century they inhabited an area of the northwestern coast of present-day Oregon from the mouth of the Columbia River south to Tillamook Head, Oregon. The tribe is first reported in the 1792 journals of Robert Gray and was later encountered at the mouth of Columbia in 1805 by the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In 1805, the northwest tip of what is now Oregon was inhabited by the Clatsop Indians. The tribe consisted of about four hundred people, and occupied three villages on the southern side of the Columbia river. Like their neighbors, the Chinooks, the Clatsops were a flourishing people, and enjoyed plentiful amounts of fish and fur. They had few enemies, and fought few wars.

Coboway, chief of one of the villages, was the only Clastop leader to make recorded contact with the Corps of Discovery. On December 12, 1805, Coboway visited the expedition at Fort Clatsop, which was still under construction. He exchanged some goods, including a sea otter pelt, for fishhooks and a small bag of Shoshone tobacco. Over the rest of the winter, Coboway would be a frequent and welcome vistor to Fort Clatsop.

The Clatsops also aided the Corps both in preparing for and dealing with the Northwest winter. They informed Lewis and Clark that there was a good amount of elk on the south side of the Columbia, information that influenced the Corps to build Fort Clatsop where they did. When the expedition’s food supplies were running low, the Clatsops informed the Corps that a whale had washed ashore some miles to the south.

Relations between the Clatsops and the expedition went well through the duration of the Americans’ stay. The only negative incident between the two groups – the expedition’s theft of a Clatsop canoe – was concealed from the Clatsops. At the expedition’s departure from Fort Clatsop on March 22, 1806, Lewis wrote in his journal that Coboway “has been much more kind an[d] hospitable to us than any other indian in this neighbourhood.” Because of his friendship with the expedition, Coboway was left Fort Clatsop and all its furniture by Lewis and Clark.

The Clatsop are a small tribe of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. In the early 19th century they inhabited an area of the northwestern coast of present-day Oregon from the mouth of the Columbia River south to Tillamook Head, Oregon. The tribe is first reported in the 1792 journals of Robert Gray and was later encountered at the mouth of Columbia in 1805 by the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In 1805, the northwest tip of what is now Oregon was inhabited by the Clatsop Indians. The tribe consisted of about four hundred people, and occupied three villages on the southern side of the Columbia river. Like their neighbors, the Chinooks, the Clatsops were a flourishing people, and enjoyed plentiful amounts of fish and fur. They had few enemies, and fought few wars.

Coboway, chief of one of the villages, was the only Clastop leader to make recorded contact with the Corps of Discovery. On December 12, 1805, Coboway visited the expedition at Fort Clatsop, which was still under construction. He exchanged some goods, including a sea otter pelt, for fishhooks and a small bag of Shoshone tobacco. Over the rest of the winter, Coboway would be a frequent and welcome vistor to Fort Clatsop.

The Clatsops also aided the Corps both in preparing for and dealing with the Northwest winter. They informed Lewis and Clark that there was a good amount of elk on the south side of the Columbia, information that influenced the Corps to build Fort Clatsop where they did. When the expedition’s food supplies were running low, the Clatsops informed the Corps that a whale had washed ashore some miles to the south.

Relations between the Clatsops and the expedition went well through the duration of the Americans’ stay. The only negative incident between the two groups – the expedition’s theft of a Clatsop canoe – was concealed from the Clatsops. At the expedition’s departure from Fort Clatsop on March 22, 1806, Lewis wrote in his journal that Coboway “has been much more kind an[d] hospitable to us than any other indian in this neighbourhood.” Because of his friendship with the expedition, Coboway was left Fort Clatsop and all its furniture by Lewis and Clark.

Thursday, April 18, 2019

Native American Mother And Child In A Canoe by Cassilly Adams (1843-1921)

Cassilly Adams (American artist, 1843-1921) Indian Mother And Child In A Canoe

A descendant of President John Adams, Kassilli or Cassilly Adams (1843-1921) was born in Zanesville, Ohio. His father, William Adams, was an amateur painter. Young Cassilly studied painting at the Academy of Art in Boston and Cincinnati Art School. During the Civil War he served in the US Navy. From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries. By 1880, Adams was living in St. Louis. In 1884, the artist created a monumental canvas depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn (death of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army and its famous commander George Custer) - "Custer's Last Fight." The painting was exhibited across the country, and then was purchased by the company "Anheuser-Busch" and later donated to the Seventh Cavalry. After the restoration of the original during the Great Depression, it was exhibited in the officers' club at Fort Bliss (Texas), and June 13, 1946 was burned in a fire. Despite the success of "Custer's Last Fight," Adams remained a relatively unknown artist. He focused on the image of Indians American West Plains life, worked as an illustrator, a farmer. He died Kassilli Adams May 8, 1921 near Indianapolis.

A descendant of President John Adams, Kassilli or Cassilly Adams (1843-1921) was born in Zanesville, Ohio. His father, William Adams, was an amateur painter. Young Cassilly studied painting at the Academy of Art in Boston and Cincinnati Art School. During the Civil War he served in the US Navy. From Europe to the Atlantic coast of America & on to the Pacific coast during the 17C-19C, settlers moved West encountering a variety of Indigenous Peoples who had lived on the land for centuries. By 1880, Adams was living in St. Louis. In 1884, the artist created a monumental canvas depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn (death of the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army and its famous commander George Custer) - "Custer's Last Fight." The painting was exhibited across the country, and then was purchased by the company "Anheuser-Busch" and later donated to the Seventh Cavalry. After the restoration of the original during the Great Depression, it was exhibited in the officers' club at Fort Bliss (Texas), and June 13, 1946 was burned in a fire. Despite the success of "Custer's Last Fight," Adams remained a relatively unknown artist. He focused on the image of Indians American West Plains life, worked as an illustrator, a farmer. He died Kassilli Adams May 8, 1921 near Indianapolis.

Wednesday, April 17, 2019

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Kiowa Chief, His Wife, and Two Warriors

George Catlin (1796 –1872) Kiowa Chief, His Wife, and Two Warriors

The Kiowa emerged as a distinct people in their original homeland of the northern Missouri River Basin. Searching for more lands of their own, the Kiowa traveled southeast to the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota & Wyoming around 1650. In the Black Hills region, the Kiowa lived peacefully alongside the Crow Indians, with whom they long maintained a close friendship, organized themselves into 10 bands, & numbered around 3000. Pressure from the Ojibwe in the north woods & edge of the great plains in Minnesota forced the Cheyenne, Arapaho, & later the Sioux westward into Kiowa territory around the Black Hills. The Kiowa were pushed south by the invading Cheyenne who were then pushed westward out of the Black Hills by the Sioux. Eventually the Kiowa obtained a vast territory on the central & southern great plains in western Kansas, eastern Colorado, most of Oklahoma including the panhandle, & the Llano Estacado in the Texas Panhandle & eastern New Mexico.[33] In their early history, the Kiowa traveled with dogs pulling their belongings until horses were obtained through trade & raid with the Spanish & other Indian nations in the southwest.

In the early spring of 1790 at the place that would become Las Vegas, New Mexico, a Kiowa party led by war leader Guikate, made an offer of peace to a Comanche party while both were visiting the home of a mutual friend of both tribes. This led to a later meeting between Guikate & the head chief of the Nokoni Comanche. The two groups made an alliance to share the same hunting grounds & entered into a mutual defense pact & became the dominant inhabitants of the Southern Plains. From that time on, the Comanche & Kiowa hunted, traveled, & made war together. In addition to the Comanche, the Kiowa formed a very close alliance with the Plains Apache (Kiowa-Apache), with the two nations sharing much of the same culture & participating in each other's annual council meetings & events. The strong alliance of southern plains nations kept the invading Spanish from gaining a strong colonial hold on the southern plains & eventually forced them completely out of the area, pushing them eastward & south past the Rio Grande into present day Mexico.