Today's lacrosse resembles games played by various Native American communities. These include games called dehuntshigwa'es in Onondaga ("men hit a rounded object"), da-nah-wah'uwsdi in Eastern Cherokee ("little war"), Tewaarathon in Mohawk language ("little brother of war"), baaga`adowe in Ojibwe ("bump hips") and kabucha in Choctaw.

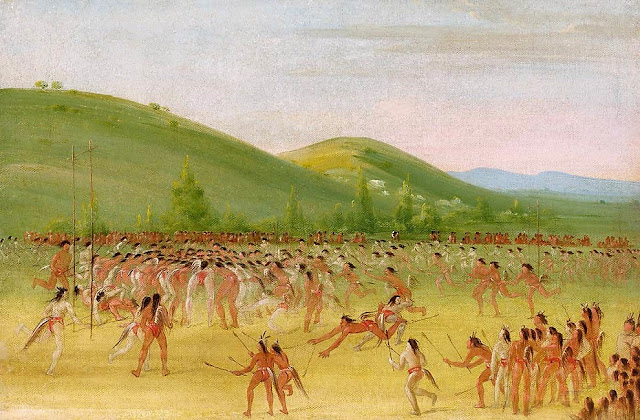

George Catlin (1796-1872) Ball-play of the Choctaw--Ball Down 1834

George Catlin (1796-1872) Ball Players

Native American ball games often involved hundreds of players. Early lacrosse games could last several days. As many as 100 to 1,000 men from opposing villages or tribes might participate. The games were played in open plains located between 2 villages, and the goals could range from 500 yards (460 m) to several miles apart.

George Catlin (1796-1872) Ball-play of the Women

The history of Lacrosse seems to begin among North American Indian tribes. As early as the 1400s, the Iroquois, Huron, Algonquin and other tribes were playing the game. In its beginnings lacrosse, then called baggataway, was a game that was part religious ritual and part military training. In early games, just running up and down the field was a great feat. Goals could be as far as 500 yards to half a mile apart and no sidelines limited the playing area. Games lasted 2 to 3 days with “time outs” between sundown and sunup. Teams were vying to move a small, deerskin ball past their opponent’s goal. Players used 3-4 foot long sticks with small nets on the end to throw, catch and carry the ball.

George Catlin (1796-1872) Ball-play Dance by Choctaw, 1834.

Lacrosse had spiritual significance for the Native Americans. A match started with a face off during which players would hold their sticks in the air and shout out to get the gods’ attention. Games were sometimes played to appeal to the gods for healing or to settle disputes between tribes. The sport became a diplomatic tool saving tribes from more violent warfare. Native Americans used at least one game of lacrosse as a military ploy. The Sauk and Ojibway Indian Tribes staged a lacrosse match outside the gates of Fort Michilimackinac in what is now Michigan, in June of 1763. The soldiers witnessing the game were fascinated by the rough play and the speedy back-and-forth engagement. Captivated, they began to wager with one another and cheer for their favorites. The troops were so absorbed by the play, that they were not aware that Indian women had been sneaking weapons into the fort and up toward the ring of spectators. The Indian women stood near the fort with weapons hidden under their shawls & blankets. The men moved the action of the game toward the fort and, whoops, sent the ball over the wall. The Indians threw down their lacrosse sticks, took up the weapons and stormed the fort. French missionaries are responsible for giving the sport its name. Missionaries thought the stick used by Canadian Indian tribes looked like the crosier, or le crosse, carried by bishops.

Fort Michilimackinac Lacrosse 1763

The following article presents an excellent overview & brings lacrosse into the 20C.

THE HISTORY OF LACROSSE

By Thomas Vennum Jr., Author of American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War

Lacrosse was one of many varieties of indigenous stickball games being played by American Indians at the time of European contact. Almost exclusively a male team sport, it is distinguished from the others, such as field hockey or shinny, by the use of a netted racquet with which to pick the ball off the ground, throw, catch and convey it into or past a goal to score a point. The cardinal rule in all varieties of lacrosse was that the ball, with few exceptions, must not be touched with the hands.

Early data on lacrosse, from missionaries such as French Jesuits in Huron country in the 1630s and English explorers, such as Jonathan Carver in the mid-eighteenth century Great Lakes area, are scant and often conflicting. They inform us mostly about team size, equipment used, the duration of games and length of playing fields but tell us almost nothing about stickhandling, game strategy, or the rules of play. The oldest surviving sticks date only from the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and the first detailed reports on Indian lacrosse are even later. George Beers provided good information on Mohawk playing techniques in his Lacrosse (1869), while James Mooney in the American Anthropologist (1890) described in detail the "[Eastern] Cherokee Ball-Play," including its legendary basis, elaborate rituals, and the rules and manner of play.

Given the paucity of early data, we shall probably never be able to reconstruct the history of the sport. Attempts to connect it to the rubber-ball games of Meso-America or to a perhaps older game using a single post surmounted by some animal effigy and played together by men and women remain speculative. As can best be determined, the distribution of lacrosse shows it to have been played throughout the eastern half of North America, mostly by tribes in the southeast, around the western Great Lakes, and in the St. Lawrence Valley area. Its presence today in Oklahoma and other states west of the Mississippi reflects tribal removals to those areas in the nineteenth century. Although isolated reports exist of some form of lacrosse among northern California and British Columbia tribes, their late date brings into question any widespread diffusion of the sport on the west coast.

On the basis of the equipment, the type of goal used and the stick-handling techniques, it is possible to discern three basic forms of lacrosse—the southeastern, Great Lakes, and Iroquoian. Among southeastern tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, Yuchi and others), a double-stick version of the game is still practiced. A two-and-a half foot stick is held in each hand, and the soft, small deerskin ball is retrieved and cupped between them. Great Lakes players (Ojibwe, Menominee, Potawatomi, Sauk, Fox, Miami, Winnebago, Santee Dakota and others) used a single three-foot stick. It terminates in a round, closed pocket about three to four inches in diameter, scarcely larger than the ball, which was usually made of wood, charred and scraped to shape. The northeastern stick, found among Iroquoian and New England tribes, is the progenitor of all present-day sticks, both in box as well as field lacrosse. The longest of the three—usually more than three feet—it was characterized by its shaft ending in a sort of crook and a large, flat triangular surface of webbing extending as much as two-thirds the length of the stick. Where the outermost string meets the shaft, it forms the pocket of the stick.

George Catlin (1796-1872) Ball-play of the Choctaw--ball up 1834

Apart from its recreational function, lacrosse traditionally played a more serious role in Indian culture. Its origins are rooted in legend, and the game continues to be used for curative purposes and surrounded with ceremony. Game equipment and players are still ritually prepared by conjurers, and team selection and victory are often considered supernaturally controlled. In the past, lacrosse also served to vent aggression, and territorial disputes between tribes were sometimes settled with a game, although not always amicably. A Creek versus Choctaw game around 1790 to determine rights over a beaver pond broke out into a violent battle when the Creeks were declared winners. Still, while the majority of the games ended peaceably, much of the ceremonialism surrounding their preparations and the rituals required of the players were identical to those practiced before departing on the warpath.

For the Cherokee, lacrosse had serious ceremonial aspects and accompanying rituals, including dances and certain taboos. Pictured in this 1889 photograph is the Cherokee Ballplayers’ Dance on Qualla Reservation in North Carolina. In the ceremony before the game, the women’s dance leader (left) beats a drum and the men’s dance leader (right) shakes a gourd rattle. The ballplayers, carrying ball sticks, circle counterclockwise around the fire. A number of factors led to the demise of lacrosse in many areas by the late nineteenth century. Wagering on games had always been integral to an Indian community's involvement, but when betting and violence saw an increase as traditional Indian culture was eroding, it sparked opposition to lacrosse from government officials and missionaries. The games were felt to interfere with church attendance and the wagering to have an impoverishing effect on the Indians. When Oklahoma Choctaw began to attach lead weights to their sticks around 1900 to use them as skull-crackers, the game was outright banned.

Meanwhile, the spread of nonnative lacrosse from the Montreal area eventually led to its position today worldwide as one of the fastest growing sports (more than half a million players), controlled by official regulations and played with manufactured rather than hand-made equipment—the aluminum shafted stick with its plastic head, for example. While the Great Lakes traditional game died out by 1950, the Iroquois and southeastern tribes continue to play their own forms of lacrosse. Ironically, the field lacrosse game of nonnative women today most closely resembles the Indian game of the past, retaining the wooden stick, lacking the protective gear and demarcated sidelines of the men's game, and tending towards mass attack rather than field positions and offsides.

Bibliography:

Culin, Stewart. "Games of the North American Indians." In Twenty-fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1902-1903, pp. 1-840. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907.

Fogelson, Raymond. "The Cherokee Ball Game: A Study in Southeastern Ethnology." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1962.

Vennum, Thomas Jr. American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War. Washington, DC and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

+Ball-play+of+the+Choctaw--Ball+Up.jpg)

+Ball+Players.jpg)

+Ball-play+Dance+by+George+Catlin,+1834..jpg)